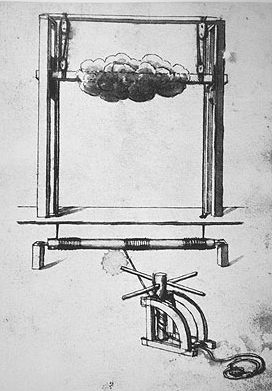

Through his innovative stage machines, architect Nicola Sabbatini summoned lightning, fire, hell, storms, gods, and clouds to the sets of 17th-century Venetian operas. The effect could be spectacular — characters braved moving waves, flew through the air, and descended into the underworld.

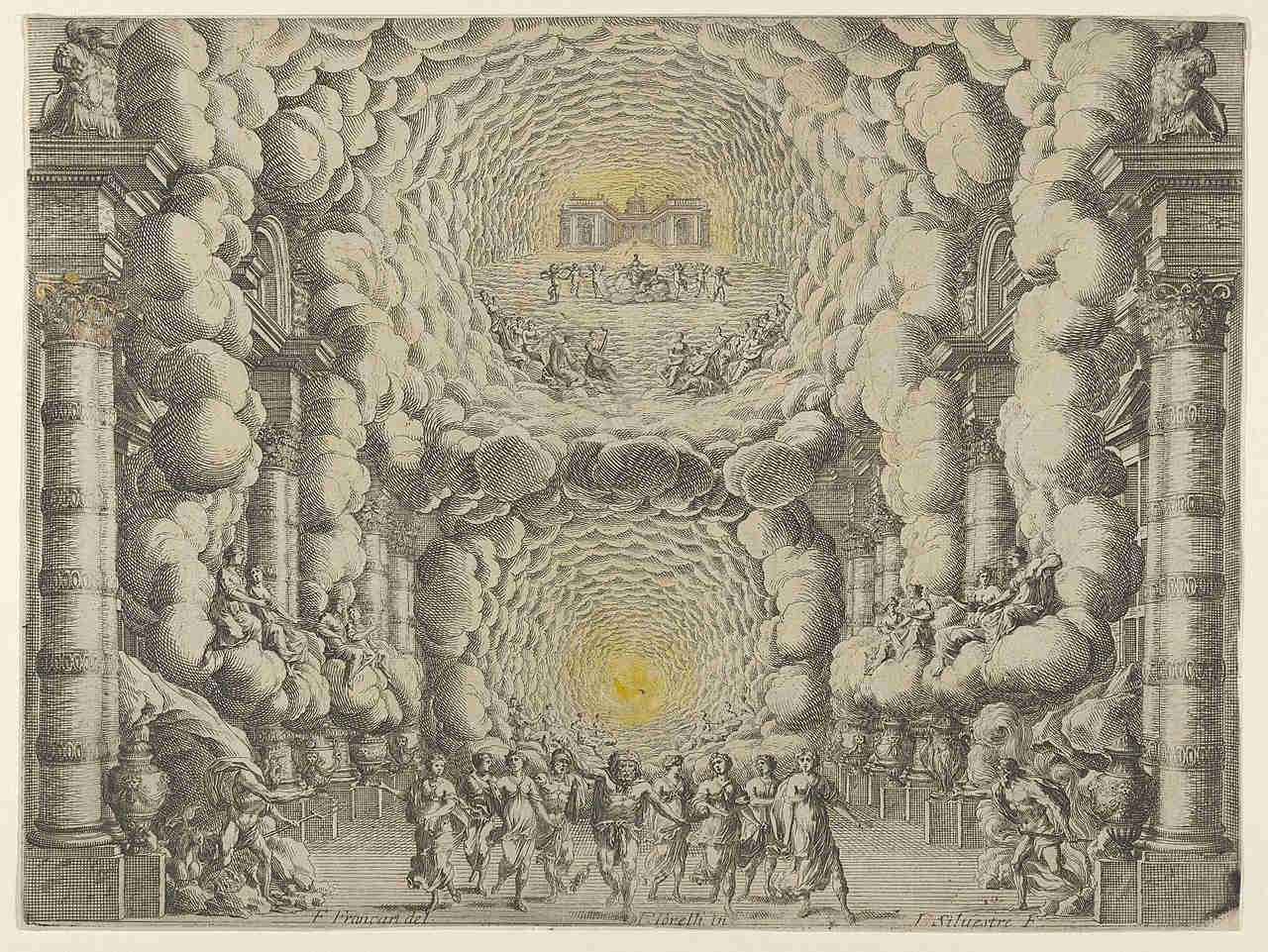

His illusions, which came to be known as scènes à l’italienne, were best viewed from “the prince’s seat,” the center of the seventh row, where “all the objects in the scene appear better … than from any other place.” The scene above, undertaken with stage designer Giacomo Torelli, depicts Apollo’s palace as a city among the clouds in Francesco Sacrati’s La Venere Gelosa (1643).

But they didn’t always work. Where one libretto read, “Here one sees descend an enormous machine, which arrives at the level of the gloria from the level of the floor of the stage, forming a majestic stairway of clouds, by which Jove descends, accompanied by a multitude of deities and celestial goddesses,” one critic wrote, “A stairway of clouds? For shame! / pardon me, architect: / it was a ladder to climb to the roof.”