Mr. Smith goes to Atlantic City to gamble for a weekend. To guard against bad luck, he sets a policy at the start: In every game he plays, he’ll bet exactly half the money he has at the time, and he’ll make all his bets at even odds, so he’ll have an equal chance of winning and of losing this amount. In the end he wins the same number of games that he loses. Does he break even?

Two Dire Punishments

Under Roman law, subjects found guilty of patricide were subjected to poena cullei, the “penalty of the sack” — they were sewn into a leather sack with a snake, a cock, a monkey, and a dog and thrown into water.

In his Life of Artaxerxes, Plutarch describes an ancient Persian method of execution known as scaphism in which vermin devour a victim trapped between mated boats:

Taking two boats framed exactly to fit and answer each other, they lie down in one of them the malefactor that suffers, upon his back; then, covering it with the other, and so setting them together that the head, hands, and feet of him are left outside, and the rest of his body lies shut up within, then forcing him to ingest a mixture of milk and honey before pouring all over his face and body. They then keep his face continually turned towards the sun; and it becomes completely covered up and hidden by the multitude of flies that settle on it. And as within the boats he does what those that eat and drink must needs do, creeping things and vermin spring out of the corruption and rottenness of the excrement, and these entering into the bowels of him, his body is consumed.

Happily Plutarch seems to have based his account on a report by the Greek historian Ctesias, whose reliability has been questioned, so perhaps this never happened.

All Right Then

In the 1970’s, a student of Maoist inclination asked [Columbia philosopher Sidney Morgenbesser] if he disagreed with Chairman Mao’s saying that a proposition can be true or false at the same time. Dr. Morgenbesser replied, ‘I do and I don’t.’

From Morgenbesser’s 2004 New York Times obituary.

Unquote

“I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.” — Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda’s Thumb, 1980

Four Glasses

Martin Gardner published this puzzle in his “Mathematical Games” column in Scientific American in February 1979. You’re blindfolded and sitting before a lazy susan. On each corner is a glass. Some are right side up and some upside down. On each turn you can inspect any two glasses and, if you choose, reverse the orientation of either or both of them. After each turn the lazy susan will be rotated through a random angle. When all four glasses have the same orientation, a bell will sound. How can you reach this goal in a finite number of turns?

Cameo

Grip, the talking raven in Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge, was based on a real bird, a pet who lived in the family’s Marylebone home, where she buried items in the garden, terrorized the dog, bit the children, and tore at the family carriage. She died in 1841 after ingesting some lead-based paint, and Dickens wrote her into the novel, which appeared later that year.

Interestingly, when Edgar Allan Poe reviewed the story for Graham’s Magazine, he remarked that “The raven … might have been made more than we see it … Its croaking might have been prophetically heard in the course of the drama.” In 1842, when the two authors met in Philadelphia, Poe was said to be “delighted” that Grip had been based on a real bird.

Poe’s famous poem appeared three years later, and scholars generally agree that Grip had inspired the “ebony bird” — in Dickens’ novel the raven had repeated the phrases “Never say die” and “Nobody” and is described as “tapping at the door” and “knocking softly at the shutter.”

Today Grip’s remains are on display in Philadelphia’s Parkway Central Library, where they may inspire yet more writings.

Noted

Band Practice

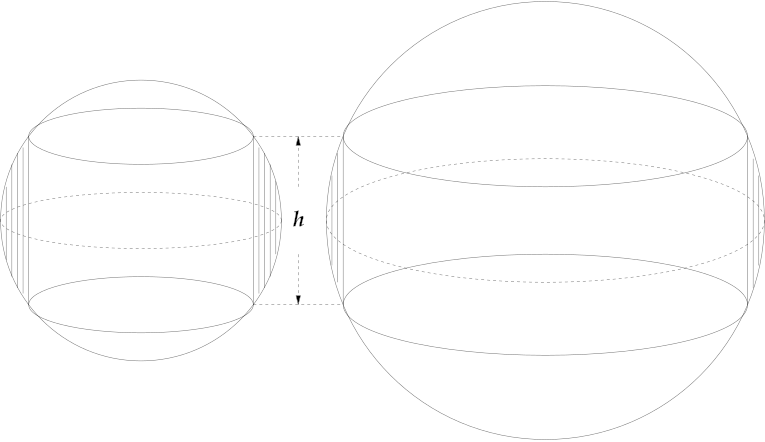

Drill a hole straight through the center of a sphere, leaving a band in the shape of a napkin ring. Suppose the height of this band is h. Now take a sphere of a different size and drill a hole through that, contriving the hole’s width so that its depth is again h. Remarkably, the two napkin rings will have the same volume.

As the sphere expands, the band must grow both wider and thinner, and it turns out that these two effects exactly cancel one another. It’s called the napkin ring problem.

Passing Through

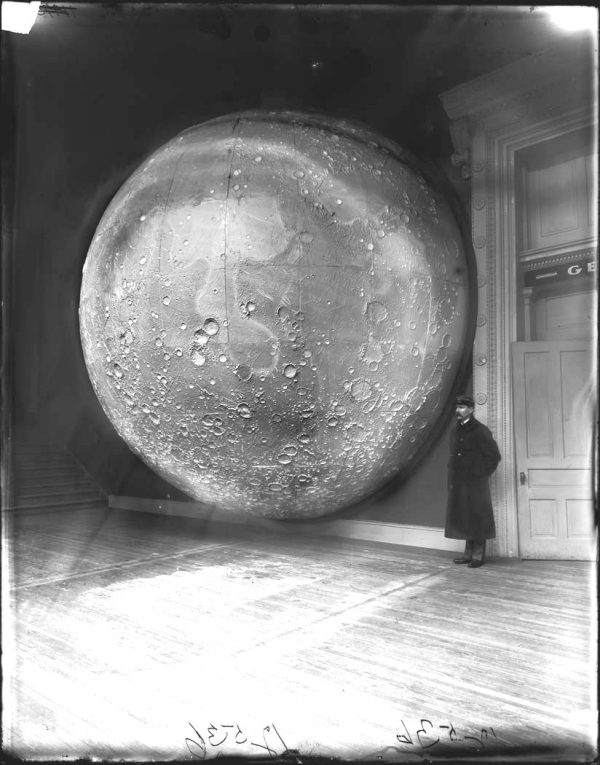

Just a striking image: German astronomer Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt prepared a plaster moon for the Field Columbian Museum in 1898. From the Field Museum Library.

Flat Devotion

William Linkhaw sang so badly that a grand jury indicted him for disrupting his church’s services. At trial in August 1872, a witness imitated Linkhaw’s singing style and provoked “a burst of prolonged and irresistible laughter, convulsing alike the spectators, the Bar, the jury and the Court.”

It was in evidence that the disturbance occasioned by defendant’s singing was decided and serious; the effect of it was to make one part of the congregation laugh and the other mad; that the irreligious and frivolous enjoyed it as fun, while the serious and devout were indignant.

Linkhaw protested that he felt a duty to worship God. The jury fined him a penny, but the North Carolina Supreme Court set aside the verdict, observing that Linkhaw had had no malicious intent. Justice Thomas Settle wrote, “It would seem that the defendant is a proper subject for the discipline of his church, but not for the discipline of the Courts.”

In 1906 a wit wrote, “although the proof did show / That Linkhaw’s voice was awful / The judges found no valid ground / For holding it unlawful.”