“It is astonishing that there should still be found today people who do not believe that there are witches.” — Henry Bouget, 1602

Rule of Paw

Canadian cats have their own parliament. In the same precinct of Ottawa where the human legislature meets, Irène Desormeaux erected a feline equivalent in the 1970s. The cats are all spayed or neutered, they get free inoculations and medical care, and the whole thing is run by volunteers using personal donations.

The Happiest Place on Earth

Yes, it’s The Rescuers, and yes, that’s a topless woman in the window.

Disney discovered her in two frames of the film’s 1999 home video release, but apparently she’d been there since the film’s premiere in 1977.

The studio recalled 3.4 million videotapes and released a cleaned-up version two months later. If they know who did it, they’re not saying.

Double-Booked

In 1975, Émile Ajar won the Prix Goncourt for his novel The Life Before Us. The French literary prize is awarded only once to each author, so Ajar could not be recognized again.

Or so you’d think. It turned out that Ajar was a pen name of Romain Gary, who had already won the prize in 1956.

Gary/Ajar remains the only author to win the medal twice.

Hokie Justice

Mark Lindsey had just graduated from the Virginia Tech architecture school in 1982 when his firm was asked to design an addition to the football stadium at VT’s rival, the University of Virginia.

“There was a V-shaped opening at the end of the stadium,” he told the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “And I had a late-night inspiration that the best thing to put in this V-shaped opening was a T.”

To everyone’s surprise, UVA bought it, and Bryant Hall opened in 1985. In fact, though the VT logo was clearly visible from the air, UVA officials didn’t notice it until it was pointed out. They replaced the building in 1999.

“It’s been a great little story to tell at parties,” Lindsey said.

In a Word

barbermonger

n. a vain man

The Prisoners’ Paradox

Three condemned prisoners share a cell. A guard arrives and tells them that one has been pardoned.

“Which is it?” they ask.

“I can’t tell you that,” says the guard. “I can’t tell a prisoner his own fate.”

Prisoner A takes the guard aside. “Look,” he says. “Of the three of us, only one has been pardoned. That means that one of my cellmates is still sure to die. Give me his name. That way you’re not telling me my own fate, and you’re not identifying the pardoned man.”

The guard thinks about this and says, “Prisoner B is sure to die.”

Prisoner A rejoices that his own chance of survival has improved from 1/3 to 1/2. But how is this possible? The guard has given him no new information. Has he?

(In Mathematical Ideas in Biology [1968], J. Maynard Smith writes, “This should be called the Serbelloni problem since it nearly wrecked a conference on theoretical biology at the villa Serbelloni in the summer of 1966.”)

Writing Weather

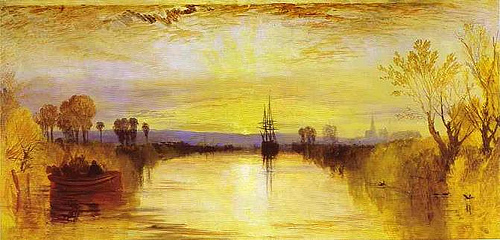

1816 is known as “the year without a summer” — the eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora flung huge amounts of volcanic dust into the atmosphere, dropping temperatures worldwide and giving the sky a sallow cast that’s visible in Turner’s landscapes of the period (above).

It was a great calamity for farmers, but a boon for horror literature — the “wet, ungenial summer” forced Mary Shelley and John Polidori indoors on their Swiss holiday, where they wrote both Frankenstein and The Vampyre.

Oops

In 1800, robber and housebreaker Pierre Coignard was sentenced to 14 years’ hard labor in the prison at Toulon. After five years he escaped, journeyed to Catalonia, assumed the identity of a local nobleman, won glory fighting in the Spanish ranks, entered the French army, rose to become a decorated colonel …

… and was recognized in Paris by one of his former cellmates.

He was tried, convicted, and returned to the same prison he had escaped 18 years earlier.

The Triple Deal

Take any twenty-one cards, and ask a person to choose one from them. [Deal] them in three heaps, and ask the person who selected the card in which heap it is placed. Gather them up, and put the heap containing the chosen card between the other two. Do this twice more, and the chosen card will be found the eleventh from the top.

— Alfred Elliott, The Playground and the Parlour, 1868