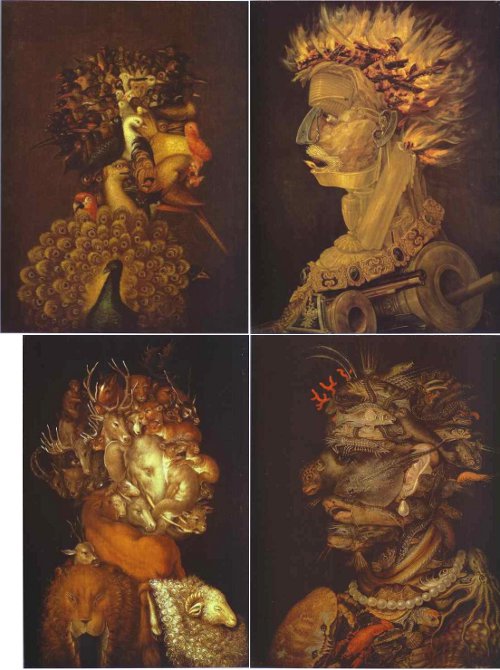

Three years after personifying the four seasons, Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527-1593) did the same for the four elements.

“There is no unemployed force in Nature,” wrote Emerson. “All decomposition is recomposition.”

Three years after personifying the four seasons, Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527-1593) did the same for the four elements.

“There is no unemployed force in Nature,” wrote Emerson. “All decomposition is recomposition.”

In certain professions there is no shortage of new applicants but, on the contrary, many people who are waiting to enter …; half of the people currently employed are below average, and for each of them leaving their job would not cause enormous hardship. … [Therefore] Half of the people should each consider giving up their place for such a newcomer. … If I am correct, a great many people have a substantial moral and personal reason to retire, even if it were thought too morally demanding to expect them to do so. To put it bluntly: for a great many people, the best professional action that they can currently take is to leave their profession.

— Saul Smilansky, Ten Moral Paradoxes, 2007

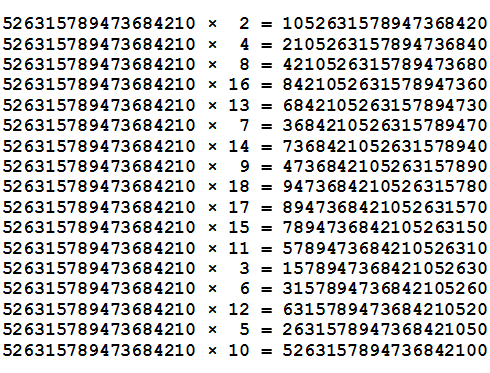

In 1891, J.H. Hooper found what he thought was a buried headstone on his farm in Bradley County, Tenn. On excavating it he found that the stone was part of a sandstone wall, about 16 feet of whose length was covered with unreadable marks arranged in wavy, nearly parallel lines.

A small sensation ensued. “Some of these forms recall those on the Dighton Rock,” wrote A.L. Rawson that year in the Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, “and may belong to the same age. How many other hidden inscriptions there may be in this, the geologically oldest continent, it is impossible to say but delightful to conjecture.”

Others thought they saw duplicates among the characters, as well as drawings of birds and animals. Could the inscription be Hebrew? Had the Lost Tribes of Israel somehow found their way to prehistoric Tennessee? No, as it turns out: Today it’s thought the marks were made … by mollusks.

A couple were going to be married, and had proceeded as far as the church door: the gentleman then stopped his intended bride, and thus unexpectedly addressed her:–

‘My dear Eliza, during our courtship I have told you most of my mind, but I have not told you the whole: when we are married, I shall insist upon three things.’

‘What are they?’ asked the lady.

‘The three things are these,’ said the bridegroom: ‘I shall sleep alone, I shall eat alone, and find fault when there is no occasion: can you submit to these conditions?’

‘O yes, sir, very easily,’ was the reply, ‘for if you sleep alone, I shall not; if you eat alone, I shall eat first: and as to your finding fault without occasion, that I think may be prevented, for I will take care you shall never want occasion.’

The conditions being thus adjusted, they proceeded to the altar, and the ceremony was performed.

— The Knot Tied: Marriage Ceremonies of All Nations, 1877

Bertrand Russell explains Zeno’s paradox of the stadium:

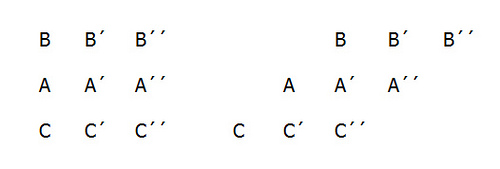

Let us suppose three drill-sergeants, A, A′, and A′′, standing in a row, while the two files of soldiers march past them in opposite directions. At the first moment which we consider, the three men B, B′, B′′, in one row, and the three men C, C′, C′′ in the other row, are respectively opposite to A, A′, and A′′. At the very next moment, each row has moved on, and now B and C′′ are opposite A′. When, then, did B pass C′? It must have been somewhere between the two moments which we supposed consecutive. It follows that there must be other moments between any two given moments, and therefore that there must be an infinite number of moments in any given interval of time.

In other words, if time is a series of consecutive instants, and motion means passing through consecutive points, then the Bs are passing the As at the fastest possible speed — one point per instant. How then is it that the Bs are passing the Cs at twice this rate? It seems, Aristotle noted, that “half the time is equal to its double.”

Two communists are sitting on the porch of a nudist colony.

One says, “Have you read Marx?”

The other says, “Yes, I think it’s these wicker chairs.”

(Dr. Johnson abominated puns. When Boswell suggested that perhaps he couldn’t make them himself, Johnson said, “If I were punishéd for every pun I shed, there would not be left a puny shed for my punnish head.”)

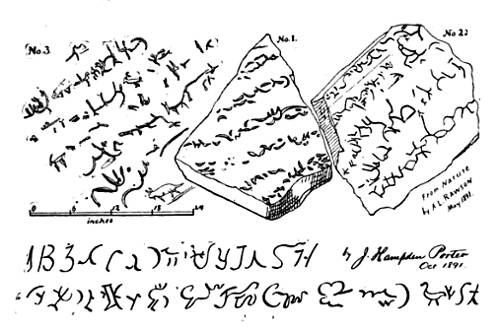

When the Chevalier de Rohan was sent to the Bastille in 1674 on suspicion of treason, he knew there was no evidence against him except what might be extracted from one other prisoner. His friends had promised to communicate the result of that examination, and in sending him some fresh clothing they wrote on one of the shirts MG DULHXCCLGU GHJ YXUJ, LM CT ULGC ALJ.

For 24 hours de Rohan puzzled over the message, but he could make no sense of it. Despairing, he admitted his guilt and was executed. What was the message?

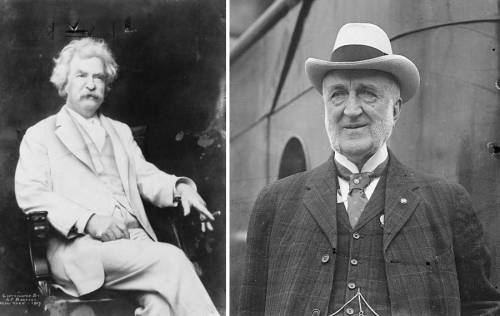

Traveling on the same ship, Mark Twain and Chauncey Depew were asked to address the dinner crowd. Twain went first and spoke for 20 minutes to great applause. Then Depew rose.

“Mr. Toastmaster and ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “before this dinner, Mark Twain and I made an agreement to trade speeches. He has just delivered my speech, and I thank you for the pleasant manner in which you received it. I regret to say that I have lost the notes of his speech and cannot remember anything he has to say.” And he sat down, to much laughter.

The next day, an Englishman found Twain in the smoking room. “Mr. Clemens,” he said, “I consider you were much imposed on last night. I have always heard that Mr. Depew is a clever man — but really, that speech of his you made last night struck me as being most infernal rot.”

In the 1970s, Forrest Ackerman sold this story to Vertex for $100:

Cosmic Report Card: Earth

F

He resold it four times for the same amount, and it’s been translated into three languages.

The “shortest horror story ever written” is usually attributed to Fredric Brown:

The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door.

Ron Smith shortened this further by changing knock to lock.