sanguisugent

adj. bloodsucking

sanguisugent

adj. bloodsucking

Naturalist George Merryweather offered a gruesome new instrument at London’s Great Exhibition in 1851: He imprisoned 12 leeches in a ring of bottles, which he capped with whalebone levers. (The bottles were arranged in a circle so that the leeches “might see one another and not endure the affliction of solitary confinement.”) When a storm approached, the agitated leeches would climb the bottles, trip the levers, and ring a bell. The more agitated this “jury of philosophical councilors,” the more frequently the bell sounded, and the more likely a storm.

After a year of experiments, Merryweather claimed great success — among other feats, the “leech barometer” foretold the disastrous storm of October 1850 51 hours before it took place. “I may here observe,” Merryweather wrote, “that I could cause a little leech, governed by its instinct, to ring Saint Paul’s great bell in London as a signal for an approaching storm.”

He proposed that the government install stations around the British coast, and nominated engineer William Reid to be inspector-general of leeches and meteorologist James Glaisher his second-in-command. Inexplicably, they turned him down. “After this,” opined Chambers’ Journal, “the Snail Telegraph looks not quite so outrageous an absurdity.”

Letter from Charles Dodgson to Nellie Bowman, Nov. 1, 1891:

C.L.D., Uncle loving your! Instead grandson his to it give to had you that so, years 80 or 70 for it forgot you that was it pity a what and: him of fond so were you wonder don’t I and, gentleman old nice very a was he. For it made you that him been have must it see you so: grandfather my was, then alive was that, ‘Dodgson Uncle’ only the. Born was I before long was that, see you, then But. ‘Dodgson Uncle for pretty thing some make I’ll now,’ it began you when, yourself to said you that, me telling her without, knew I course of and: ago years many great a it made had you said she. Me told Isa what from was it? For meant was it who out made I how know you do! Lasted has it well how and. Grandfather my for made had you macassar-Anti pretty that me give to you of nice so was it, Nellie dear my

“If you see Nobody come into the room,” he wrote to another girl, “please give him a kiss from me.”

She oped the portal of the palace,

She stole into the garden’s gloom;

From every spotless snowy chalice

The lilies breathed a sweet perfume.

She stole into the garden’s gloom,

She thought that no one would discover;

The lilies breathed a sweet perfume,

She swiftly ran to meet her lover.

She thought that no one would discover,

But footsteps followed, ever near:

She swiftly ran to meet her lover

Beside the fountain crystal clear.

But footsteps followed ever near;

Ah, who is that she sees before her

Beside the fountain crystal clear?

‘T is not her hazel-eyed adorer.

Ah, who is that she sees before her,

His hand upon his scimitar?

‘T is not her hazel-eyed adorer,

It is her lord of Candahar!

His hand upon his scimitar–

Alas, what brought such dread disaster!

It is her lord of Candahar,

The fierce Sultan, her lord and master.

Alas, what brought such dread disaster!

“Your pretty lover’s dead!” he cries–

The fierce Sultan, her lord and master–

“‘Neath yonder tree his body lies.”

“Your pretty lover’s dead!” he cries–

(A sudden, ringing voice behind him);

“‘Neath yonder tree his body lies–”

“Die, lying dog! go thou and find him!”

A sudden, ringing voice behind him,

A deadly blow, a moan of hate,

“Die, lying dog! go thou and find him!

Come, love, our steeds are at the gate!”

A deadly blow, a moan of hate,

His blood ran red as wine in chalice;

“Come, love, our steeds are at the gate!”

She oped the portal of the palace.

— Clinton Scollard, Pictures in Song, 1884

John and Margaret Vivian declared bankruptcy in 1992, so they weren’t pleased when NationsBank sent them a dunning notice on a debt that had been discharged. The bank apologized, saying that a computer had generated the notice, but the Vivians received a second notice, then a third.

So Florida bankruptcy judge A. Jay Cristol held the computer in contempt of court:

ORDERED that the NationsBank computer, having been determined in civil contempt, is fined 50 megabytes of hard drive memory and 10 megabytes random access memory. The computer may purge itself of this contempt by ceasing the production and mailing of documents to Mr. and Mrs. Vivian.

The computer had no comment.

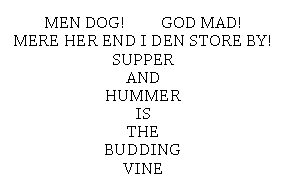

In the November 1971 issue of Word Ways, reader Solomon Golomb noted that the following placard appeared in the window of a business establishment “and was considered quite ordinary by all passers-by.” Why?

Babylas, Hilary, and Sosthenes have escaped the tower and divided their treasure into three bags. But now they must cross a river, and the boat can accommodate only two men at a time, or one man and a bag. None will trust another with his bag on the shore, but they agree that a man in the boat can be trusted to drop or retrieve a bag at either shore, as he’ll be too busy to tamper with it. How can they cross the river?

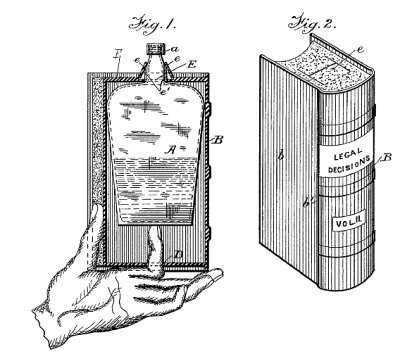

For the really determined alcoholic, in 1885 Herbert Jenner patented a liquor flask hidden in a book:

The ornamental covering [has] been made so as to entirely cover and conceal the flask from observation, and at the same time admit of ready access to its contents. … That portion of the covering representing the edges of the leaves of the book is covered with marbled paper or otherwise treated, so as to give a natural appearance.

Charmingly, the book is titled Legal Decisions.

A self-descriptive sentence by Howard Bergerson:

In this sentence, the word and occurs twice, the word eight occurs twice, the word four occurs twice, the word fourteen occurs four times, the word in occurs twice, the word occurs occurs fourteen times, the word sentence occurs twice, the word seven occurs twice, the word the occurs fourteen times, the word this occurs twice, the word times occurs seven times, the word twice occurs eight times, and the word word occurs fourteen times.

Look before you leap.

He who hesitates is lost.

Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

Out of sight, out of mind.

You’re never too old to learn.

You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.

A word to the wise is sufficient.

Talk is cheap.

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Actions speak louder than words.

The pen is mightier than the sword.

Many hands make light work.

Too many cooks spoil the broth.

Seek and ye shall find.

Curiosity killed the cat.

Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth.

Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

The best things in life are free.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

G.K. Chesterton said, “I owe my success to having listened respectfully to the very best advice, and then going away and doing the exact opposite.”