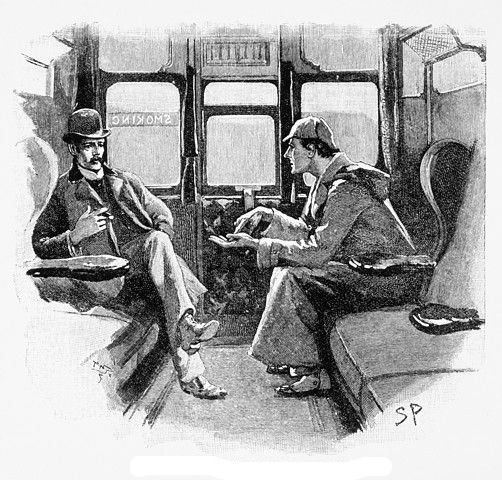

I seem to be on a Sherlock Holmes kick lately. A few oddities about Dr. Watson:

- In A Study in Scarlet he says he was wounded in the shoulder, but in The Sign of Four he says he was wounded in the leg. One theory resolves this by suggesting that he was bending over when hit, and that the bullet passed through his leg and lodged in his shoulder. (The BBC series Sherlock sidesteps the problem by saying that Watson’s limp is a psychosomatic symptom of post-traumatic stress.)

- He seems uncertain about his first name. In “The Problem of Thor Bridge,” Watson says that his dispatch box is labeled “John H. Watson, M.D.,” but in “The Man With the Twisted Lip” his wife Mary calls him “James.” Dorothy L. Sayers offers another neat resolution: Maybe his middle name is Hamish, the Scottish equivalent of James.

- It’s not clear how many times he’s been married. He certainly married Mary Morstan, whom he met in The Sign of Four. But then in “The Empty House” he refers to “my own sad bereavement,” and in “The Blanched Soldier” Holmes mentions that “The good Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife, the only selfish action which I can recall in our association.” This seems to suggest that Watson remarried after Mary’s death, but this is never made clear, and a second wife is never named.

At its annual dinner, the Sherlock Holmes literary society the Baker Street Irregulars always toasts the second Mrs. Watson. This was the toast in 2002:

Watson had a second wife

But, did he lead a double life?

He had two wounds; he had two names

(One was John, the other James).

He often claimed he dined alone

Yet quaffed whole bottlesful of Beaune.

He’d disappear for days on end

Accompanying his clever friend,

Then lame excuses where he’d been

Were published in Strand Magazine.

And so to the spouse of this pain in the ass

We raise a toast and lift our glass.

(From Roger Johnson and Jean Upton, The Sherlock Holmes Miscellany, 2012.)