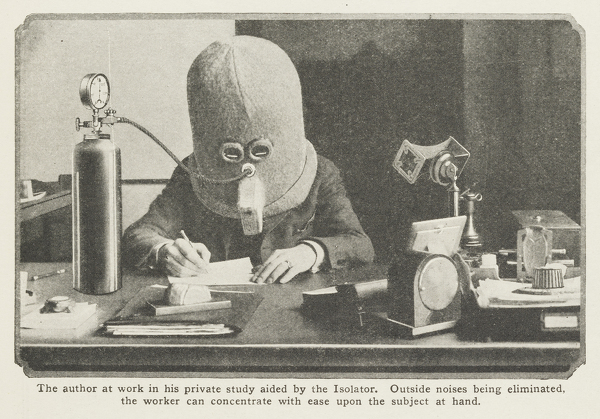

Irritated with distractions in his editorial work, Hugo Gernsback designed a helmet “to do away with all possible interferences that prey on the mind”:

The first helmet constructed as per illustration was made of wood, lined with cork inside and out, and finally covered with felt. There were three pieces of glass inserted for the eyes. In front of the mouth there is a baffle, which allows breathing but keeps out the sound. The first construction was fairly successful, and while it did not shut out all the noises, it reached an efficiency of about 75 per cent. The reason was that solid wood was used.

In a later version he omitted the wood and added an air space between layers of cotton and felt, achieving an efficiency of 90 to 95 percent. Even the eyepieces are black except for a single slit, to prevent the eyes from wandering. “With this arrangement it is found that an important task can be completed in short order and the construction of the Isolator will be found to be a great investment.”

(He even designed an ideal office, with a soundproof door, triple-paned windows, and felt-filled walls, in which to wear this — see the illustration at the link below.)

(Hugo Gernsback, “The Isolator,” Science and Invention 13:3 [July 1925], 214ff.)