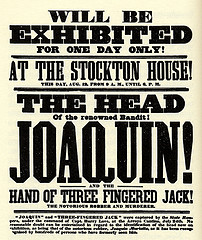

For an Old West outlaw, Black Bart had a rather poetic sensibility. Born Charles Bolles, Bart robbed stagecoaches of thousands of dollars throughout the 1870s and 1880s, but even his first victims noted his politeness — he avoided foul language and merely asked the driver to “please throw down the box.”

Eventually Bart was writing full-blown poetry to leave at the scene of each crime. He left behind this verse after one California robbery in 1877:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread

You fine-haired sons of bitches.

… and this one the following year:

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse;

And if there’s money in that box

‘Tis munny in my purse.

When Bart was released from prison in 1888, a reporter asked if he were going to return to robbing stagecoaches. “No, gentlemen,” he said, “I’m through with crime.” Another asked whether he would write more poetry. He smiled, “Now, didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”