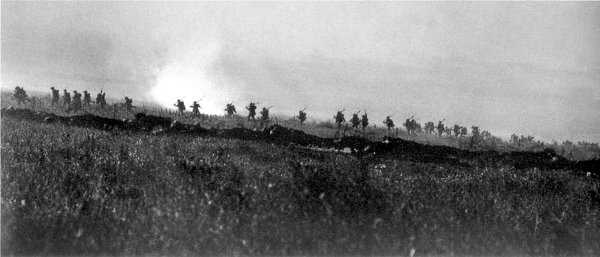

Memories of the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916:

“Before the bombardment started and while everything was peaceful, I could see through my periscope a young Englishman playing his trumpet every evening. We used to wait for this hour but suddenly there was nothing to be heard and we all hoped that nothing had happened to him.” — Feldwebel Karl Stumpf, 169th Regiment

“As the gun-fire died away I saw an infantryman climb onto the parapet into No Man’s Land, beckoning others to follow. As he did so he kicked off a football; a good kick, the ball rose and travelled well towards the German line. That seemed to be the signal to advance.” — Private L.S. Price, 8th Royal Sussex

“For some reason nothing seemed to happen to us at first; we strolled along as though walking in a park. Then, suddenly, we were in the midst of a storm of machine-gun bullets and I saw men beginning to twirl round and fall in all kinds of curious ways as they were hit — quite unlike the way actors do it in films.” — Private W. Slater, 2nd Bradford Pals

“When the English started advancing we were very worried; they looked as though they must overrun our trenches. We were very surprised to see them walking, we had never seen that before. I could see them everywhere; there were hundreds. The officers were in front. I noticed one of them walking calmly, carrying a walking stick. When we started firing, we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them. If only they had run, they would have overwhelmed us.” — Musketier Karl Blenk, 169th Regiment

“Imagine stumbling over a ploughed field in a thunderstorm, the incessant roar of the guns and flashes as the shells exploded. Multiply all this and you have some idea of the Hell into which we were heading. To me it seemed a hundred times worse than any storm.” — Private E. Houston, Public Schools Battalion

“The sound was different, not only in magnitude but in quality, from anything known to me. It was not a succession of explosions or a continuous roar; I, at least, never heard either a gun or a bursting shell. It was not a noise, it was a symphony. And it did not move. It hung over us. It seemed as though the air were full of vast and agonised passion, bursting now with groans and sighs, now into shrill screaming and pitiful whimpering, shuddering beneath terrible blows, torn by unearthly whips, vibrating with the solemn pulses of enormous wings. And the supernatural tumult did not pass in this direction or in that. It did not begin, intensify, decline and end. It was poised in the air, a stationary panorama of sound, a condition of the atmosphere, not the creation of man.” — Anonymous NCO, 22nd Manchester Rifles

It would become the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army, with 57,470 casualties. “From that moment all my religion died,” recalled Private C. Bartram of the 94th Trench Mortar Battery. “All my teaching and beliefs in God had left me, never to return.”