This item appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on Oct. 19, 1863:

Whose Father Was He?

After the battle of Gettysburg, a Union soldier was found in a secluded spot on the field, where, wounded, he had laid himself down to die. In his hands, tightly clasped, was an ambrotype containing the portraits of three small children, and upon this picture his eyes, set in death, rested. The last object upon which the dying father looked was the image of his children, and as he silently gazed upon them his soul passed away. How touching! how solemn! What pen can describe the emotions of this patriot-father as he gazed upon these children, so soon to be made orphans! Wounded and alone, the din of battle still sounding in his ears, he lies down to die. His last thoughts and prayers are for his family. He has finished his work on earth; his last battle has been fought; he has freely given his life to his country; and now, while his life’s blood is ebbing, he clasps in his hands the image of his children, and, commending them to the God of the fatherless, rests his last lingering look upon them.

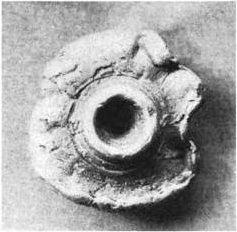

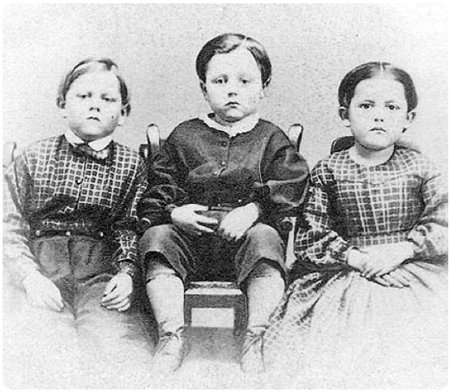

When, after the battle, the dead were being buried, this soldier was thus found. The ambrotype was taken from his embrace, and since been sent to this city for recognition. Nothing else was found upon his person by which he might be identified. His grave has been marked, however, so that if by any means this ambrotype will lead to his recognition he can be disinterred. This picture is now in the possession of Dr. Bourns, No. 1104 Spring Garden [Street], of this city, who can be called upon or addressed in reference to it. The children, two boys and a girl, are, apparently, nine, seven and five years of age, the boys being respectively the oldest and youngest of the three. The youngest boy is sitting in a high chair, and on each side of him are his brother and sister. The eldest boy’s jacket is made from the same material as his sister’s dress. These are the most prominent features of the group. It is earnestly desired that all the papers in the country will draw attention to the discovery of this picture and its attendant circumstances, so that, if possible, the family of the dead hero may come into possession of it. Of what inestimable value it will be to these children, proving, as it does, that the last thoughts of their dying father was for them, and them only.

The description was reprinted in the American Presbyterian on Oct. 29, where it was read by Philinda Humiston of Portville, N.Y., who had not heard from her husband since Gettysburg. She identified the unknown soldier as Sgt. Amos Humiston of Company C, 154th New York Volunteers. His body was removed to the Gettysburg National Cemetery, and the outpouring of sympathy for his children led to the establishment of a Soldier’s Orphan’s Home in Gettysburg in 1866.