“People think I can teach them style. What stuff it all is! Have something to say, and say it as clearly as you can. That is the only secret of style.” — Matthew Arnold

Wind Power

From a 1773 letter from Ben Franklin to Barbeu Dubourg:

When I was a boy, I amused myself one day with flying a paper kite; and approaching the bank of a pond, which was near a mile broad, I tied the string to a stake and the kite ascended to a very considerable height above the pond while I was swimming. In a little time, being desirous of amusing myself with my kite, and enjoying at the same time the pleasure of swimming, I returned, and loosing from the stake the string with the little stick which was fastened to it, went again into the water, where I found that, lying on my back and holding the stick in my hands, I was drawn along the surface of the water in a very agreeable manner. Having then engaged another boy to carry my clothes round the pond, to a place which I had pointed out to him on the other side, I began to cross the pond with my kite, which carried me quite over without the least fatigue and with the greatest pleasure imaginable. I was only obliged occasionally to halt a little in my course and resist its progress when it appeared that, by following too quick, I lowered the kite too much; by doing which occasionally I made it rise again.

“I have never since that time practiced this singular mode of swimming, though I think it not impossible to cross in this manner from Dover to Calais. The packet boat, however, is still preferable.”

Coming and Going

The Danish word for TAX is SKAT.

DIY

Born in Texarkana in 1912, Conlon Nancarrow had no access to technology that could realize the music in his head. He studied music briefly and played trumpet in venues ranging from beer halls to cruise ships, but he found himself frustrated working with human musicians. In 1940 he withdrew to Mexico City, where, working in almost complete isolation, he began composing pieces for player piano.

This expedient was “a tremendous amount of work, punching all those holes by hand, one by one, hundreds and thousands of them,” but it enabled him finally to hear his music. “I’d never heard it played. Some composers are pianists and can at least play their music on piano, but I couldn’t do even that, because I am not a pianist.”

Freed from the constraints imposed by human performers, Nancarrow’s style developed a dizzying speed, staggering complexity, and a bewildering density of ideas. “Nancarrow’s complete works could be heard in seven hours,” wrote composer Kyle Gann, “but within half that time the listener would be as exhausted as though he had consumed Mahler’s ten symphonies in a gulp.”

Gyorgy Ligeti discovered some piano pieces in a Paris record store in 1980 and became an early champion, calling the composer “the greatest discovery since Webern and Ives.” Subsequent admirers included John Cage (“Conlon’s music has such an outrageous, original character that it is literally shocking”) and Frank Zappa (“The stuff is fantastic … You’ve got to hear it. It’ll kill you”).

Nancarrow became a MacArthur fellow in 1982 and returned to writing for live ensembles, finding that the standard of musicianship had improved enormously during his 40-year exile. “Of course it’s pleasing,” he told the New York Times in 1987. “I mean, all those years I had been working now have some point. There are so many artists and writers who are doing something they think is worthwhile, and it turns out to be junk. I thought that maybe mine was the same thing, but now I see it wasn’t.”

(Thanks, Katie.)

“A Dry Quicksand”

In the southwestern corner of the desert of southern Arabia, north of the western end of Hadramaut, and approached from the little village of Sawa, is a very remarkable spot described by Wrede from his visit in 1843, whose description is reproduced in a recent number of the Revue coloniale internationale. There are here, in the waste of yellow sand, several spots covered by a grayish white dust, which swallow up every object thrown into them. One of these spots, described by Wrede, is about two miles long and a little less in breadth. It sinks gradually toward the middle and is apparently due to the work of the wind. Wrede approached it with the greatest care and sounded it with his staff. The edge is stony and falls away suddenly. When the staff was thrust into the fine material beyond the edge, almost no resistance was felt and it was as if the staff had been thrust into water. When it was passed through the fine dust lengthwise the resistance was almost imperceptible. A stone of two pounds weight or more was fastened to a cord sixty fathoms long and thrown in as far as possible. It sank at once and with increasing velocity so that at the end of five minutes the end of the cord had disappeared. The presence of Bedouins prevented any more observations. The natives believe that great treasures are buried here and are watched over by genii who pull down into the depths the unwary treasure-seeker.

— American Meteorological Journal, May 1886

Field Work

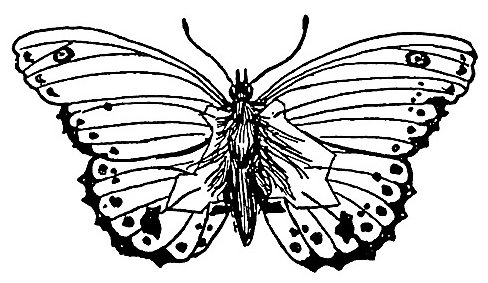

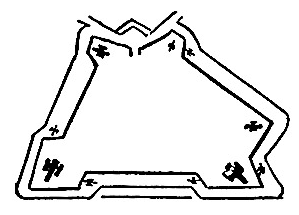

In 1891, Robert Baden-Powell wandered the mountains of Dalmatia with a butterfly net and a sketchbook. If he was accosted by one of the forts in the area, he would show his drawings to the soldiers and explain that he was hunting a particular species, and they would send him on his way.

In fact he was working as an intelligence officer for the British government. “They did not look sufficiently closely into the sketches of butterflies to notice that the delicately drawn veins of the wings were exact representations, in plan, of their own fort, and that the spots on the wings denoted the number and position of guns and their different calibres”:

The large dots denote the locations of the fort’s main guns, and the smaller show field artillery and machine-gun emplacements.

“Fortunately for us, we are as a nation considered by the others to be abnormally stupid, therefore easily to be spied upon,” he wrote in his 1915 memoir My Adventures as a Spy. “But it is not always safe to judge entirely by appearances.”

House Call

Letter from Charles Dickens to a chimney sweep, March 15, 1864:

Dear Sir,

Since you last swept my study chimney it has developed some peculiar eccentricities. Smoke has indeed proceeded from the cowl that surmounts it, but it has seemingly been undergoing internal agonies of a most distressing nature, and pours forth disastrous volumes of swarthy vapour into the apartment wherein I habitually labour. Although a comforting relief probably to the chimney, this is not altogether convenient to me. If you can send a confidential sub-sweep, with whom the chimney can engage in social intercourse, it might be induced to disclose the cause of the departure from its normal functions.

Faithfully yours,

Charles Dickens

The Conscience Fund

During the Civil War, the U.S. Treasury received a check for $1,500 from a private citizen who said he had misappropriated government funds while serving as a quartermaster in the Army. He said he felt guilty.

“Suppose we call this a contribution to the conscience fund and get it announced in the newspapers,” suggested Treasury Secretary Francis Spinner. “Perhaps we will get some more.”

Ever since then, the Treasury has maintained a “conscience fund” to which guilt-ridden citizens can contribute. In its first 20 years, the fund received $250,000; by 1987 it had taken in more than $5.7 million. One Massachusetts man contributed 9 cents for using a damaged stamp on a letter, but in 1950 a single individual sent $139,000.

In order to encourage citizens to contribute, Treasury officials don’t try to identify or punish the donors. Most donations are anonymous, and many letters are from clergy, following up confessions taken at deathbeds.

Many contributions are sent by citizens who have resolved to start anew in life by righting past wrongs, but some are more grudging. In 2004, one donor wrote, “Dear Internal Revenue Service, I have not been able to sleep at night because I cheated on last year’s income tax. Enclosed find a cashier’s check for $1,000. If I still can’t sleep, I’ll send you the balance.”

The World Backstage

This is charming — an inventory of “all the properties for my Lord Admiral’s men,” taken by theatrical impresario Philip Henslowe on March 10, 1598:

Item: 1 rock, 1 cage, 1 Hell-mouth

Item: 1 tomb of Guido, 1 tomb of Dido, 1 bedstead

Item: 8 lances, 1 pair of stairs for Phaeton

Item: 2 steeples, and 1 chime of bells, and 1 beacon

Item: 1 globe, and 1 golden sceptre; 3 clubs

Item: 2 marchpanes, and the city of Rome

Item: 1 golden fleece; 2 rackets; 1 bay-tree

Item: 1 wooden canopy; old Mahomet’s head

Item: 1 lion skin; 1 bear’s skin; and Phaeton’s limbs, and Phaeton chariot; and Argus’ head

Item: Neptune fork and garland

Item: 8 vizards; Tamburlaine bridle; 1 wooden mattock

Item: Cupid’s bow and quiver; the cloth of the sun and moon

Item: 1 boar’s head and Cerberus’ three heads

Item: 1 caduceus; 2 moss banks, and 1 snake

Item: 2 fans of feathers; Belin Dun’s stable; 1 tree of golden apples; Tantalus’ tree; 9 iron targets

Item: 1 Mercury’s wings; Tasso picture; 1 helmet with dragon; 1 shield with 3 lions; 1 elm bowl

Item: 1 lion; 2 lion heads; 1 great horse with his legs; 1 sackbut

Item: 1 black dog

Item: 1 cauldron for the Jew

Much of what we know about the business of Elizabethan theater comes from a book of accounts that Henslowe kept around the turn of the 17th century. He never mentions Shakespeare directly, but his theaters competed with the Globe.

The Parent Trap

The founder of Mother’s Day, Anna Jarvis, had no children of her own and decried the commercialization of the holiday.

Jarvis had proposed a national Mother’s Day in 1907, in part to honor her own mother. She promoted the idea with governors, congressmen, editors, and the White House, and in 1914 Woodrow Wilson set aside the second Sunday in May to honor the nation’s mothers. But the holiday was almost immediately co-opted by merchants, a turn that horrified Jarvis. “Confectioners put a white ribbon on a box of candy and advance the price just because it’s Mother’s Day,” she complained in 1924. “There is no connection between candy and this day. It is pure commercialization.”

She tried to stem the tide by legal means, incorporating herself as the Mother’s Day International Association and threatening copyright suits against what she felt were commercial celebrations. She had recommended the wearing of carnations to mark the holiday; when florists raised the price she distributed celluloid buttons instead at her own expense.

She reserved a special bitterness for sons who bought mass-produced cards for their mothers. “A maudlin, insincere printed card or ready-made telegram means nothing except that you’re too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone else in the world,” she said. “Any mother would rather have a line of the worst scribble from her son or daughter than any fancy greeting card.”

“The sending of a wire is not sufficient. Write a letter to your mother. No person is too busy to do this.”

It was hopeless. Her spirit never flagged, but her finances began to give way, and in 1943, penniless and almost blind, she was admitted to a Philadelphia hospital. Her friends pledged funds for her support, and she died in a West Chester sanitarium in 1948.