Suppose we agree that everyone has a right to life, but that a person forfeits this right when he threatens the life of another — in that case it’s permissible to kill him.

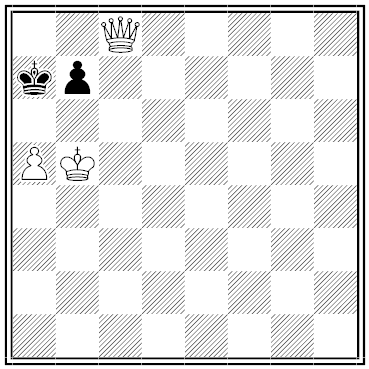

Now consider three people, A, B, and C. A aims a gun at B, B aims a gun at C, and C aims a gun at A. When A takes aim, he’s threatening another person, so he loses his own right to life. Normally in that case C would be justified in killing him, since this defends B. But B is aiming at C, which means he forfeits his own right to life … which means that A can kill him, and that C can’t kill A.

There seems no way to resolve this under the rules we’ve laid out. “Each actor has a right to life if he or she lacks a right to life and lacks a right to life if he or she has a right to life,” wrote University of Tulsa law professor Russell Christopher, who offered the puzzle in 1998. He uses it to suggest that subjective factors such as motive, belief, and knowledge must be considered when making these judgments.

(Russell Christopher, “Self-Defense and Defense of Others,” Philosophy & Public Affairs, Spring 1998)

See The Bystander Paradox.