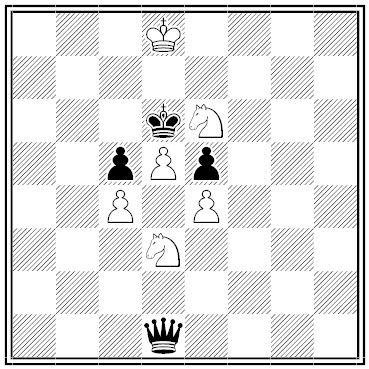

Using a 7-quart and a 3-quart jug, how can you obtain exactly 5 quarts of water from a well?

That’s a water-fetching puzzle, a familiar task in puzzle books. Most such problems can be solved fairly easily using intuition or trial and error, but in Scripta Mathematica, March 1948, H.D. Grossman describes an ingenious way to generate a solution geometrically.

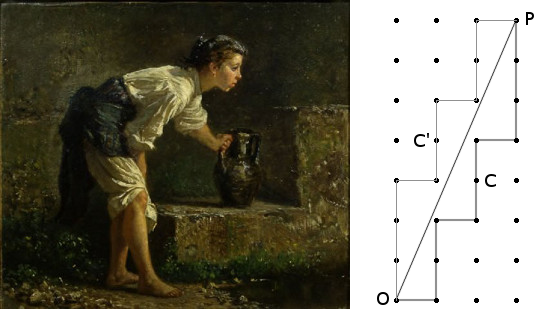

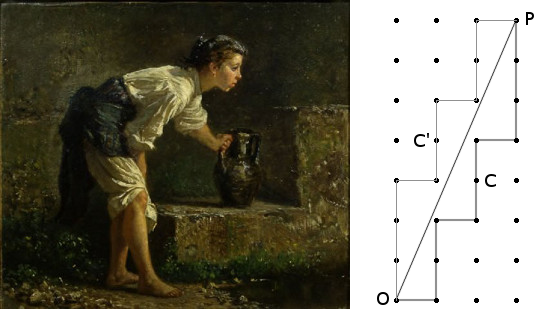

Let a and b be the sizes of the jugs, in quarts, and c be the number of quarts that we’re seeking. Here, a = 7, b = 3, and c = 5. (a and b must be positive integers, relatively prime, where a is greater than b and their sum is greater than c; otherwise the problem is unsolvable, trivial, or can be reduced to smaller integers.)

Using a field of lattice points (or an actual pegboard), let O be the point (0, 0) and P be the point (b, a) (here, 3, 7). Connect these with OP. Then draw a zigzag line Z to the right of OP, connecting lattice points and staying as close as possible to OP. Now “It may be proved that the horizontal distances from OP to the lattice-points on Z (except O and P) are in some order without repetition 1, 2, 3, …, a + b – 1, if we count each horizontal lattice-unit as the distance a.” In this example, if we take the distance between any two neighboring lattice points as 7, then each of the points on the zigzag line Z will be some unique integer distance horizontally from the diagonal line OP. Find the one whose distance is c (here, 5), the number of quarts that we want to retrieve.

Now we have a map showing how to conduct our pourings. Starting from O and following the zigzag line to C:

- Each horizontal unit means “Pour the contents of the a-quart jug, if any, into the b-quart jug; then fill the a-quart jug from the well.”

- Each vertical unit means “Fill the b-quart jug from the a-quart jug; then empty the b-quart jug.”

So, in our example, the map instructs us to:

- Fill the 7-quart jug.

- Fill the 3-quart jug twice from the 7-quart jug, each time emptying its contents into the well. This leaves 1 quart in the 7-quart jug.

- Pour this 1 quart into the 3-quart jug and fill the 7-quart jug again from the well.

- Fill the remainder of the 3-quart jug (2 quarts) from the 7-quart jug and empty the 3-quart jug. This leaves 5 quarts in the 7-quart jug, which was our goal.

You can find an alternate solution by drawing a second zigzag line to the left of OP. In reading this solution, we swap the roles of a and b given above, so the map tells us to fill the 3-quart jug three times successively and empty it each time into the 7-quart jug (leaving 2 quarts in the 3-quart jug the final time), then empty the 7-quart jug, transfer the remaining 2 quarts to it, and add a final 3 quarts. “There are always exactly two solutions which are in a sense complementary to each other.”

Grossman gives a rigorous algebraic solution in “A Generalization of the Water-Fetching Puzzle,” American Mathematical Monthly 47:6 (June-July 1940), 374-375.