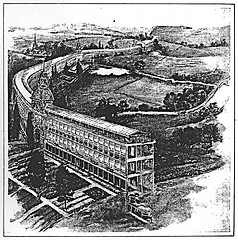

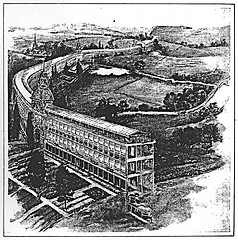

Musing on the housing problem in 1909, Edgar Chambless dreamed of laying a modern skyscraper on its side and extending it into the country. This two-story “continuous house” would be “a workable way of coupling housing and transportation into one mechanism,” with a monorail in the cellar, farmland on either side, and a path on the roof for cyclists and roller skaters.

“The Roadtown is a scheme to organize production, transportation and consumption into one systematic plan,” Chambless wrote in a 1910 manifesto. “In an age of pipes and wires, and high speed railways such a plan necessitates the building in one dimension instead of three.”

Chambless’ friend Milo Hastings promoted the idea in magazine articles, and the American Institute of Architects recognized it in a 1919 contest to present “the best solution of the housing problem.” Thomas Edison even donated the use of certain patents. Alas, though Chambless promoted his dream until his death in 1936, it never got off the drawing board.