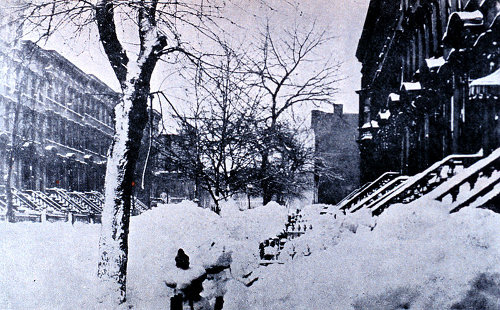

New England got unexpectedly clobbered in March 1888 when 40 inches of snow fell in a day and a half. Businesses were closed and streetcars abandoned as screaming winds whipped the drifts into house-devouring hills as deep as 50 feet. Thirty trains were paralyzed near New York City, their passengers taken in by nearby residents, and the city’s fire engines lay mired in the streets, unable to respond to calls. “Despatches between Boston and New York were sent by way of London” due to downed lines, reported the Albany Cultivator & Country Gentlemen, and “for two hours on Tuesday people crossed the East river on an ice floe brought up by the tide.”

The forecast had been “clearing and colder, preceded by light snow.”