The American Chess Bulletin of October 1917 contains a puzzle story about a boastful player who entered a local club claiming to have beaten one of the best players in the county.

Our first question was: ‘What odds did he give you?’

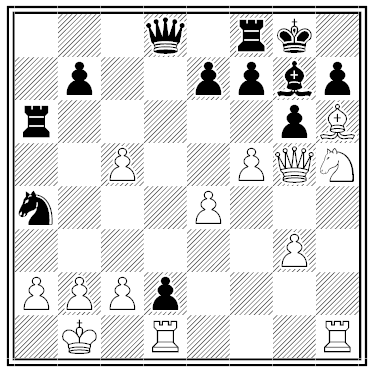

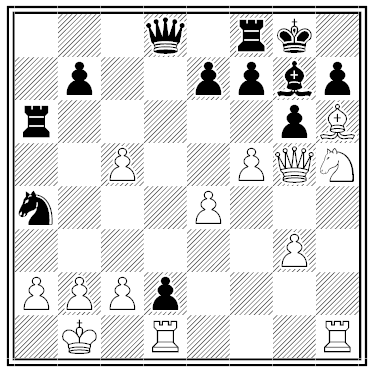

‘Why, none, of course,’ was the reply. ‘Topnotch was White, and he set up a fierce King’s side attack on my castled K. I had almost given up all hope when I saw that if I could only get my Kt to QR5, and he went on with his attack, I had a mate. So on my 15th move I played Kt-QR5. As I hoped, he overlooked the mate which he could have stopped with a move, and played 16 Kt-KR5, and then, of course, I mated. That is the position.’

And he set it up with the air of a conqueror.

We looked at it, saw the mate (a very commonplace one, by the way), and were turning away, when the Problemist, who was the most ‘fed up’ of us all, said in his quietest voice:

‘S—, you are a beautiful–Ananias.’

We started in surprise; it was so unlike him.

S—, with a red face and heated manner, said: ‘What do you mean? I give you my word of honor that was the position after White’s 16th move.’

‘I don’t dispute it; but still you are not telling the truth.’ And he proceeded to demonstrate to our satisfaction he was right.

During this period S— disappeared and I think it unlikely that we shall receive another visit from him.

Now, what did the Problemist demonstrate?

“Can our solvers unravel this mystery?” wrote the editors. “It is plain that the Problemist synthetically deduced that by no possibility could S— have met this precise position in the course of orthodox chess play.”

Alas, I don’t have the solution! If S— is telling the truth, then in the diagram above the black knight must have moved from b6 and the white knight from f4. Black’s mate would have been something like 16. … Nc3+ 17. bxc3 Qb6+ 18. cxb6 Rxb6+ 19. Ka1 Bxc3#. But none of these observations seems to lead anywhere. Any ideas?

UPDATE: A number of readers have analyzed this, and the strong consensus is that the position above cannot have been reached in 16 moves, as S— says it did. I had dismissed this possibility when the Problemist said “I don’t dispute it,” thinking this meant he accepted S—‘s contended move totals, but now I think that remark meant merely that the Problemist thinks S— generally dishonest. Thanks to everyone who saw more deeply than I did.

SECOND UPDATE: Wait. Another reader points out that perhaps the idea is that White’s position can be reached in 16 moves — if he gave knight odds. This is much more satisfying — the Problemist isn’t disputing the number of moves; he’s pointing out that Topnotch had offered to play with a significant handicap. This would embarrass the boastful S—, giving the whole story a satisfying punchline. It also explains why S— is asked explicitly about odds at the start, and it illuminates the rather canny phrasing about “orthodox” chess play. I’ll bet this is it.