quiritation

n. a cry for help

Can Do

In 1921, chemists at Arthur D. Little Inc. reduced 100 pounds of sows’ ears to glue, converted it to gelatin, forced it into fine strands, and wove these into a purse “of the sort which ladies of great estate carried in medieval days — their gold coin in one end and their silver coin in the other.”

“We made this silk purse from a sow’s ear because we wanted to, because it might serve as an example to clients who come to us with their ambitions or their troubles, and also as a contribution to philosophy,” they reported. “Things that everybody thinks he knows only because he has learned the words that say it, are poisons to progress.”

Limerick

“I must leave here,” said Lady De Vere,

“For these damp airs don’t suit me, I fear.”

Said her friend: “Goodness me!

If they don’t agree

With your system, why eat pears, my dear?”

— Anonymous

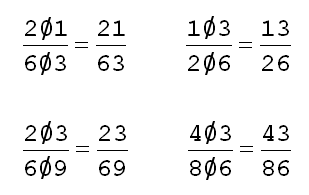

Canceling Zeros

Yellow Peril

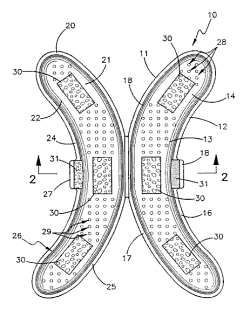

David Agulnik’s “banana protective device,” patented in 2003, is intended “for storing and transporting a banana carefully.” The hinged cover is padded “to allow the user to carry the banana in a safe manner so that it remains fresh and is protected from becoming bruised.”

“I understand the inventor of the bagpipes was inspired when he saw a man carrying an indignant, asthmatic pig under his arm,” wrote Alfred Hitchcock. “Unfortunately, the man-made sound never equalled the purity of the sound achieved by the pig.”

Monkey Business

A few years before World War I, Albert Marr discovered a baboon on his farm in Pretoria, South Africa. The two became such good friends that Marr took “Jackie” with him when he joined the Third South African Infantry Regiment, and the baboon became company mascot, with rations, a pay book, and his own uniform.

In August 1915 the two sailed for the war, where they saw front-line action against the Turks and Germans and participated in an Egyptian campaign. In 1916 Marr was hit in the Battle of Agagia, and the medical team arrived to find Jackie licking the wound.

Marr and Jackie were both wounded in April 1918, and Jackie’s leg was amputated, but he made a full recovery and was promoted to corporal and awarded a medal for valor. (In 1973 Marr showed Jackie’s discharge papers to a Johannesburg reporter. He was listed as “bilingual.”) In 1919 Jackie took part in a London victory procession, riding a captured howitzer. Then he retired to Marr’s farm, where he died in 1921.

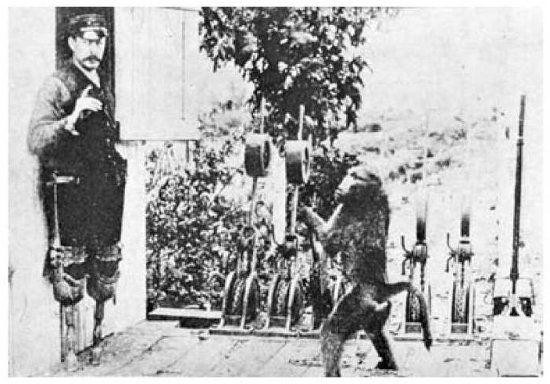

In other baboon employment news, I’ve found some more details about Jack the monkey signalman, whom I first wrote about in 2005. In her 2007 book Baboon Metaphysics, University of Pennsylvania primatologist Dorothy L. Cheney confirms that in the late 1800s railway guard James “Jumper” Wide lost his feet in a train accident and sought help with his work as a signalman at Uitenhage on the line between Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. He encountered a young baboon that had been trained to drive an ox wagon, bought him of his owner, and trained him to work as a signalman:

Each track was assigned a different number. If the driver gave one, two, or three blasts, Jack switched the signals in the appropriate manner, altering the direction of travel so that oncoming trains would not collide. If the driver gave four blasts, Jack collected the key to the coal shed and carried it out to the driver. His performance was so unerringly correct that he earned the name ‘Jack the Signalman.’

Cheney writes that when an astonished passenger complained, Jumper and Jack were dismissed, but then Jumper convinced the officials to test Jack’s skills rigorously, and he did so well that he was rehired and given daily rations and an employment number. He (Jack) died of tuberculosis in 1890.

“Long Walk on Water”

Capt. Charles W. Oldrieve to-day accomplished the feat of walking on the water from Cincinnati to New Orleans, a distance of 1,600 miles, in forty days, lacking forty-five minutes, thereby winning a wager of $5,000.

Oldrieve met with an accident just before reaching the goal, at the head of Canal Street, that nearly cost him his life. His big wooden shoes suddenly slid outward and the water walker turned turtle. His wife, who accompanied him all the way in a rowboat, rescued the Captain.

Oldrieve left Cincinnati Jan. 1 at noon on a wager that he would walk to New Orleans in forty days. At the falls above Louisville he was delayed for twenty-four hours, and that time, it was agreed, should be allowed for. Oldrieve was in motion only during daylight, lying over every night at the various landings. He was equipped with shoes made of cedar 4 feet 5 inches long, 5 inches broad, and several inches deep. In a gasoline boat preceding the water walker were Capt. J.W. Weatherington of Dallas, Texas, who backed Oldrieve, and Arthur Jones, who represented Edward Williams of Boston, who laid the wager.

— New York Times, Feb. 11, 1907

Express

On June 12, 1940, a man strolled onto the platform at Ireland’s Dingle light railway station and asked some workers when the next train would depart for Tralee.

The men stared at him, and one said, “The last train for Tralee left here 14 years ago. I reckon it might be another 14 years before the next train will leave.”

Two hours later the man, Walter Simon, was in a local jail cell. It turned out he was a German spy who had landed that evening by U-boat at Dingle Bay. His spying career was over.

The Better Man

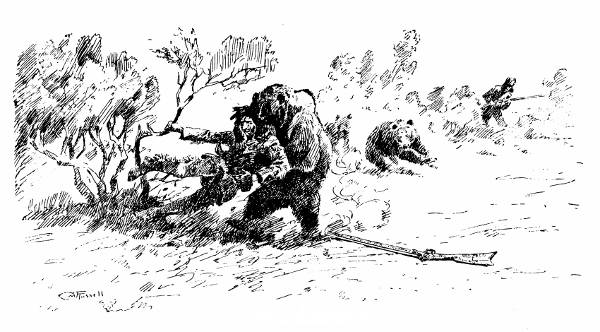

In 1822, frontiersman Hugh Glass joined a corps of 100 “enterprising young men” to ascend the Missouri River on a fur-trapping expedition. At the Grand River he was attacked by a grizzly bear; he and his companions managed to kill it, but Glass was badly mauled. The expedition’s leader offered $40 for volunteers to remain with Glass until he died or could travel. The two men who accepted this charge, John Fitzgerald and Jim Bridger, waited a short interval and then simply took Glass’ belongings and rejoined the expedition, reporting that they’d buried the body.

Glass awoke mutilated, alone, and unprovisioned 200 miles from the nearest settlement. He crawled south for six weeks, foraging on berries, roots, and the carcasses of buffalo, before he reached the Cheyenne River, where he fashioned a raft and floated to Fort Kiowa on the Missouri. Then he set out to seek revenge.

He found Bridger on the Yellowstone near the mouth of the Bighorn River, and decided to spare him because of his youth (Bridger had been only 17 when he’d abandoned Glass). He found Fitzgerald at Fort Atkinson, where he was serving as a private in the Sixth Infantry. George Yount recounts the climax:

Glass found the recreant individual, who had so cruelly deserted him, when he lay helpless & torn so shockingly by the Grizzly Bear–He also there recovered his favorite Rifle–To the man he only addressed himself as he did to the boy– ‘Go false man & answer to your own conscience & to your God;–I have suffered enough in all reason by your perfidy–You was well paid to have remained with me until I should be able to walk–You promised to do so–or to wait my death & decently bury my remains–I heard the bargain–Your shameful perfidy & heartless cruelty–but enough–Again I say, settle the matter with your own conscience & your God.’

He told Fitzgerald’s commanding officer, “I reckon the skunk ain’t worth shooting after all.”

Unquote

“Our ignorance of history makes us libel our own times. People have always been like this.” — Flaubert