merry-go-sorry

n. a tale that evokes joy and sadness simultaneously

chantpleure

v. to sing and weep at the same time

merry-go-sorry

n. a tale that evokes joy and sadness simultaneously

chantpleure

v. to sing and weep at the same time

Letter to the Times, Jan. 15, 1915:

Sir,

May I add another illustration to those which have already appeared in your columns, showing how near two lives can bring together events which seem so far apart? I remember my father telling me how, when he was attending a country grammar school in 1805, one day the master came in, full of a strange excitement, and exclaimed, ‘Boys, we’ve won a great victory!’ Then he stopped, burst into tears, and added, ‘But Nelson — Nelson is killed!’ When I was myself a boy Waterloo was a recent event, and even ‘the ’45’ was remembered and talked about.

In a few weeks I shall be 85, but I can still ride my bicycle.

William Wood, DD

Harry Mathews composed this limerick:

Young Dick, always eager to eat,

Denied stealing the fish eggs, whereat,

Caning him for a liar,

His pa ate the caviar

And left Dicky digesting the caveat.

Shouldn’t it rhyme?

Henry Hudson made this curious journal entry in the Canadian arctic, June 15, 1610:

This morning one of our company looking overboard saw a mermaid; and calling up some of the company to see her, one more came up, and by that time she was come close to the ship’s side, looking earnestly on the men. A little after, a sea came and overturned her. From the navel upward, her back and breasts were like a woman’s, as they say that saw her; her body as big as one of us; her skin very white; and long hair hanging down behind, of colour black. In her going down they saw her tail, which was like the tail of a porpoise, and speckled like a mackerel. Their names that saw her were Thomas Hilles and Robert Rayner.

“Whatever explanation be attempted of this apparition,” wrote Philip Gosse, “the ordinary resource of seal or walrus will not avail here. Seals and walruses must have been as familiar to these polar mariners as cows to a dairy-maid. Unless the whole story was a concerted lie between the two men, reasonless and objectless, — and the worthy old navigator doubtless knew the character of his men, — they must have seen, in the black-haired, white-skinned creature, some form of being as yet unrecognized.”

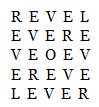

REVEL EVER, EVE! O EVE, REVEL EVER!

That sentence, composed by J.A. Lindon, can reproduce itself in two ways — it’s a conventional palindrome, and it produces a natural word square:

Last year, University of Queensland psychology undergraduate Sean Murphy was collecting images of faces while preparing an experiment. As he skimmed through them, he noticed that they began to appear grotesque and deformed, though when viewed individually they appeared normal and even attractive. (The demonstration above uses photographs of celebrities.)

“The effect seems to depend on processing each face in light of the others,” writes grad student Matthew Thompson, who published the result last year with Murphy and Jason Tangen. “By aligning the faces at the eyes and presenting them quickly, it becomes much easier to compare them, so the differences between the faces are more extreme. If someone has a large jaw, it looks almost ogre-like. If they have an especially large forehead, then it looks particularly bulbous. We’re conducting several experiments right now to figure out exactly what’s causing this effect.”

(Tangen, J. M., Murphy, S. C., & Thompson, M. B. (2011). Flashed face distortion effect: Grotesque faces from relative spaces. Perception, 40, 628-630.)

Claudette is born in 1950 and dies in an accident in 2000. If the accident had not occurred she would lived until 2035. We think of this as a misfortune because her life has been cut short — she has lost 35 years.

But it’s equally true that Claudette might have been born in 1915 and enjoyed another 35 years of life in that way. Why don’t we regard this as equally tragic? “We feel uncomfortable with the idea that her late birth is as great a misfortune for Claudette as her premature death,” writes philosopher Fred Feldman. “Why is this?”

Lucretius wrote, “Think too how the bygone antiquity of everlasting time before our birth was nothing to us. Nature therefore holds this up to us as a mirror of the time yet to come after our death. Is there aught in this that looks appalling, aught that wears an aspect of gloom? Is it not more untroubled than any sleep?” Why are we more troubled at a lost future than a lost past?

Most of the civilians who died in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor were killed by American antiaircraft shells. “There was so much excitement and confusion,” harbor worker John Garcia told Studs Turkel for The Good War, his oral history of World War II. “Some of our sailors were shooting five-inch guns at the Japanese planes. You just cannot down a plane with a five-inch shell. They were landing in Honolulu, the unexploded naval shells. They have a ten-mile range. They hurt and killed a lot of people in the city.”

Garcia spent three days at the base dealing with the aftermath of the attack. When he returned to Honolulu, “they told me that a shell had hit the house of my girl. We had been going together for, oh, about three years. Her house was a few blocks from my place. At the time, they said it was a Japanese bomb. Later we learned it was an American shell. She was killed. She was preparing for church at the time.”

“While an author is yet living, we estimate his powers by his worst performance; and when he is dead, we rate them by his best.” — Samuel Johnson