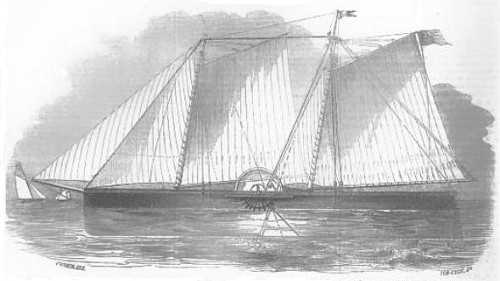

Scientific American examined a novel idea in 1854: a jointed ship whose fore and aft sections can rise and fall independently on the waves. The ship would then flex with each swell, and a chain extended between the masts could drive a paddlewheel amidships. “The hope is cherished that this Bender, whether in the form of a small boat for harbor use, or in a vessel of larger size, will demonstrate the practicability of using the wave power in moving against a head-wind.”

I don’t know how far they pursued the idea. A shipbuilder named George Steers declared himself “ready to undertake the construction of such a vessel for any parties that may apply to him.”