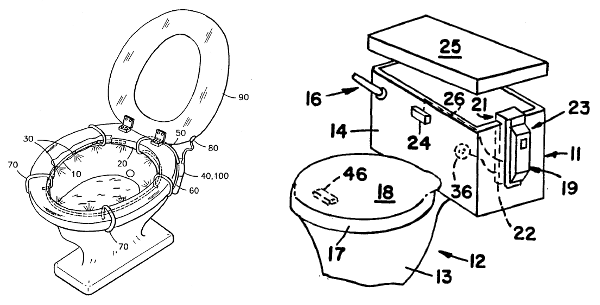

Brooke Pattee’s “night light for a toilet,” patented in 1993, mounts a tube filled with electrical lamps under the upper rim of a toilet bowl so that users can use the bathroom without fumbling in the dark or being blinded by the overhead light.

Blake Warrington’s “toilet seat cover position alarm,” patented in 1989, sounds an alarm if the seat cover is not lowered after the toilet is flushed. “The alarm has the practical effect of conditioning persons who use the toilet to routinely close the toilet seat cover.”