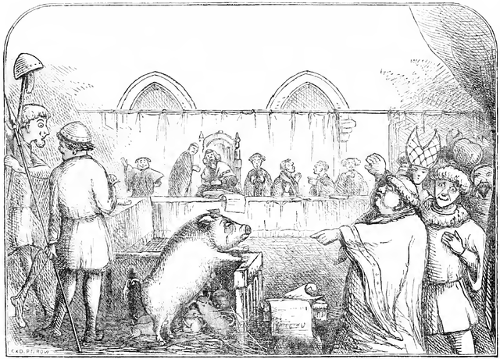

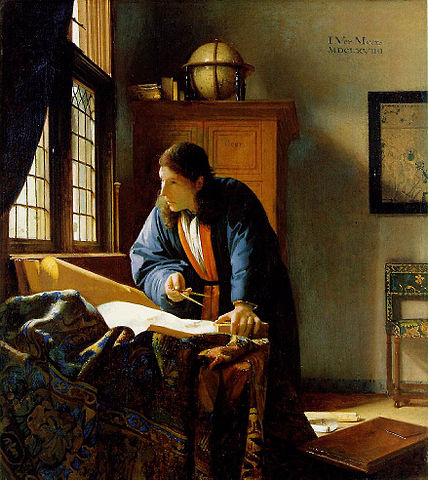

Starting in the 1970s, neurobiologist Otto-Joachim Grüsser spent 10 years collating the light sources in 2,124 paintings selected at random from Western art originating between the 14th and 20th centuries. He found that in most paintings considered Western works of art, especially those painted around the time of the Scientific Revolution, the light falls from the left.

“At the beginning of modern Western art during the early Gothic period, a preference for diffuse illumination or light sources distributed around the painted scene was found,” Grüsser noted. “In a minority of paintings from the fourteenth century that show a clear light direction, a bias to the left side is present. This left-sided preference increased at the expense of diffuse or middle light sources up to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and declined thereafter. In the twentieth century, the diffuse or middle type of light distribution again became dominant.”

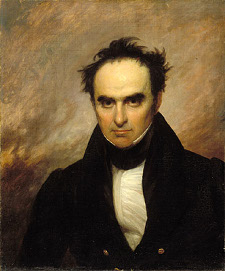

It’s not clear what to make of this. It seems reasonable that a right-handed artist might favor light falling from the left, but why should this vary with time? Grüsser found that the left-handed Leonardo da Vinci applied light sources from varying angles, and Hans Holbein the Younger, also a dominant left-hander, favored light falling from the right.

“From such observations in the works of these two left-handed painters who painted, drew, and wrote with the left hand, one gains the impression that the distribution of left, middle, and right light direction in left-handed painters deviates significantly from the average distribution of light found in the paintings of other contemporary painters. It would be interesting to study the drawings and paintings of other confirmed left-handed artists, who worked exclusively with the left hand.”

(Otto-Joachim Grüsser, Thomas Selke, and Barbara Zynda, “Cerebral Lateralization and Some Implications for Art, Aesthetic Perception, and Artistic Creativity,” in Ingo Rentschler, Barbara Herzberger, and David Epstein, Beauty and the Brain, 1988.)