Here are five new lateral thinking puzzles to test your wits and stump your friends — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Here are five new lateral thinking puzzles to test your wits and stump your friends — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

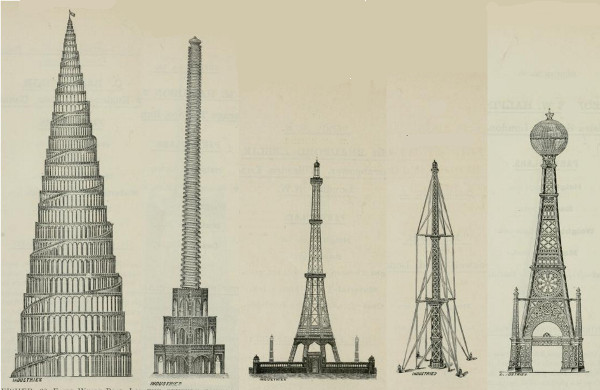

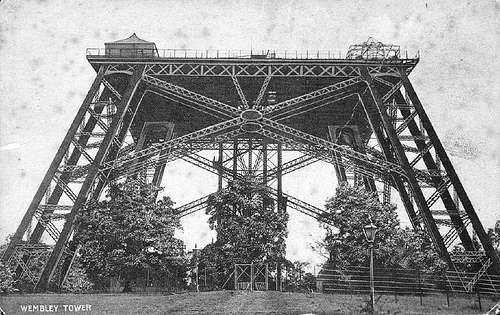

In 1890, inspired by France’s new Eiffel Tower, railway entrepreneur Sir Edward Watkin proposed building an even larger tower at Wembley as the centerpiece of a new amusement park there. He sponsored an architectural design competition that attracted 68 designs inspired by everything from the Tower of Pisa to the Great Pyramid of Giza. The winning design, number 37 (center), was to measure 366 meters tall, 45.8 meters taller than Eiffel’s tower. Foundations were laid in 1892, but funding troubles forced a redesign and in the end only the first stage was finished (below). The site was closed in 1902 and the aborted tower was dynamited five years later, but the surrounding park remained popular — it’s now the site of Wembley Stadium.

(Thanks, Meaghan.)

About 30 miles south of Washington D.C., on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, lies a curious collection of lozenge-shaped islands, the remains of a mighty fleet of wooden steamships built hurriedly during World War I and made obsolete by the end of the war. The unused ships became the center of a political scandal, “the grandest white elephant” ever built, and for decades the government and various salvage companies dithered over what to do with them. Eventually nature herself decided the question: The sunken hulls had consolidated and enriched the sediment in which they lay, creating a valuable new ecosystem. So the armada remains where it is, the largest collection of wrecked ships in the Western Hemisphere.

(Thanks, Craig.)

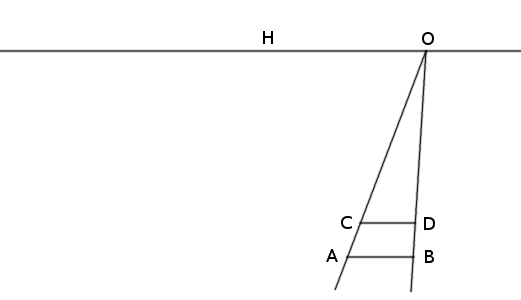

AB and CD are consecutive ties across a pair of railroad tracks that appear to meet at O on the horizon, H. If the ties are parallel to the horizon and are equally spaced along the tracks, how can we draw the next tie in this perspective figure?

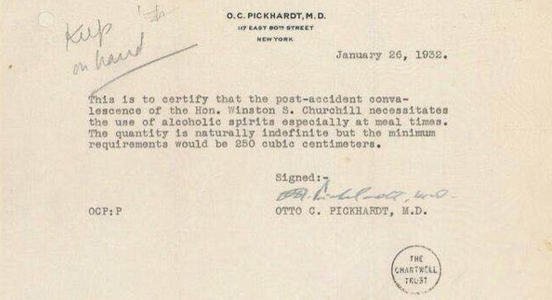

After being struck by a car in January 1932, Winston Churchill found himself laid up in New York at the height of Prohibition. He convinced his attending physician to write the prescription above.

“I neither want it [brandy] nor need it,” he once said, “but I should think it pretty hazardous to interfere with the ineradicable habit of a lifetime.”

As military and computer technology exploded in the early 1960s, Raytheon compiled a helpful list of 400 “space-age” abbreviations:

CHAMPION — Compatible Hardware And Milestone Program for Integrating Organizational Needs

COED — Computer Operated Electronic Display

DASTARD — Destroyer Anti-Submarine Transportable ARray Detector

PIPER — Pulsed Intense Plasma for Exploratory Research

It published the list in a booklet titled ABbreviations and Related ACronyms Associated with Defense, Astronautics, Business, and RAdio-electronics — or ABRACADABRA for short.

Spanish artist Jaume Plensa created El Alma del Ebro, above, for a 2008 exposition in Zaragoza on water and sustainable development. (The Ebro River passes through the city.) Visitors can pass in and out of the 11-meter seated figure, but no one has discovered a meaning in the letters that compose it.

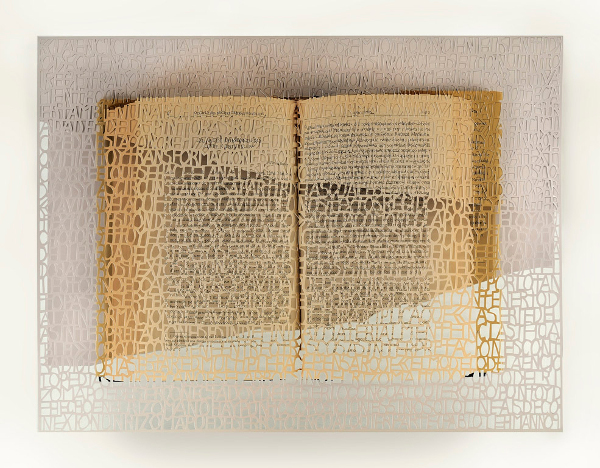

Argentine artist Pablo Lehmann cuts words out of (and into) paper and fabric — he spent two years fashioning an entire apartment out of his favorite philosophy books. Reading and Interpretation VIII, above, is a photographic print of Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Garden of Forking Paths” into which Lehmann has cut his own text — a meditation on “the concept of ‘text.'”

In 2011, Buenos Aires native Marta Minujin built a seven-story “Tower of Babel” on a public street to celebrate the city’s designation as a “world book capital.” The tower, 82 feet tall, was made of 30,000 books donated by readers, libraries, and 50 embassies. They were given away to the public after the exhibition.

California high school student Derek Hollowood created this function after considering recurrence relations:

h(-10) = 0.987654321 h(-9) = 0.87654321 h(-8) = 0.7654321 h(-7) = 0.654321 h(-6) = 0.54321 h(-5) = 0.4321 h(-4) = 0.321 h(-3) = 0.21 h(-2) = 0.1 h(-1) = 0 h(0) = 0 h(1) = 1 h(2) = 12 h(3) = 123 h(4) = 1234 h(5) = 12345 h(6) = 123456 h(7) = 1234567 h(8) = 12345678 h(9) = 123456789

(Thanks to Chris Smith for the tip.)

When I was 10 years old, a time machine appeared in my bedroom and my older self emerged and tried to kill me. He failed, of course, as his own existence must have shown him he would. But ever since I’ve wondered: This means that someday I myself must travel back to that bedroom and try to kill my younger self. And why would I ever do that?

This is not a logical or a metaphysical problem, but a psychological one. I can imagine being someday so depressed or ashamed or angry at myself that I’m motivated to travel back and try to erase my own existence. But I already know that the gun will jam. What earthly reason, then, could I have to go through the motions of a failed assassination? (Certainly we can imagine cases of amnesia, mistaken identity, etc., where such an action would make sense, but we’re interested in the basic straightforward case in which a time traveler interacts with his younger self — which surely would happen if time travel were possible.)

It seems that I must be motivated, somehow, in order for the appointment to take place, and yet the motivation seems to have no source. “In the present case, we have actions coming from nowhere, in the sense that no one decides, in the usual way, to perform them (or decides that they should be performed), and yet they are performed nonetheless,” writes University of Sydney philosopher Nicholas J.J. Smith. “The psychology of self-interaction is essentially different from that of interaction with others — because the former, but not the latter, involves the problem of agents knowing what they will decide to do, before they decide to do it.”

(Nicholas J.J. Smith, “Why Would Time Travelers Try to Kill Their Younger Selves?”, The Monist 88:3 [July 2005], 388-395.)

In 2006, Florida amended its constitution to say that any future amendments must have the approval of 60 percent of the voters.