Psychoanalyst Robert Lindner received a remarkable client at his Baltimore practice: “Kirk Allen” had read a series of science fiction novels and “In some weird and inexplicable way I knew that what I was reading was my biography.” (Lindner never revealed which series this was, but some have theorized that it was the Barsoom books of Edgar Rice Burroughs, which describe the adventures of an American Confederate veteran on Mars.)

Allen believed that he could assume his fictional identity at will and was spending part of his life on another planet. In an effort to understand his own history he’d compiled his life story, working from the books and supplementing the account with his own invented memories. Lindner asked to see this work:

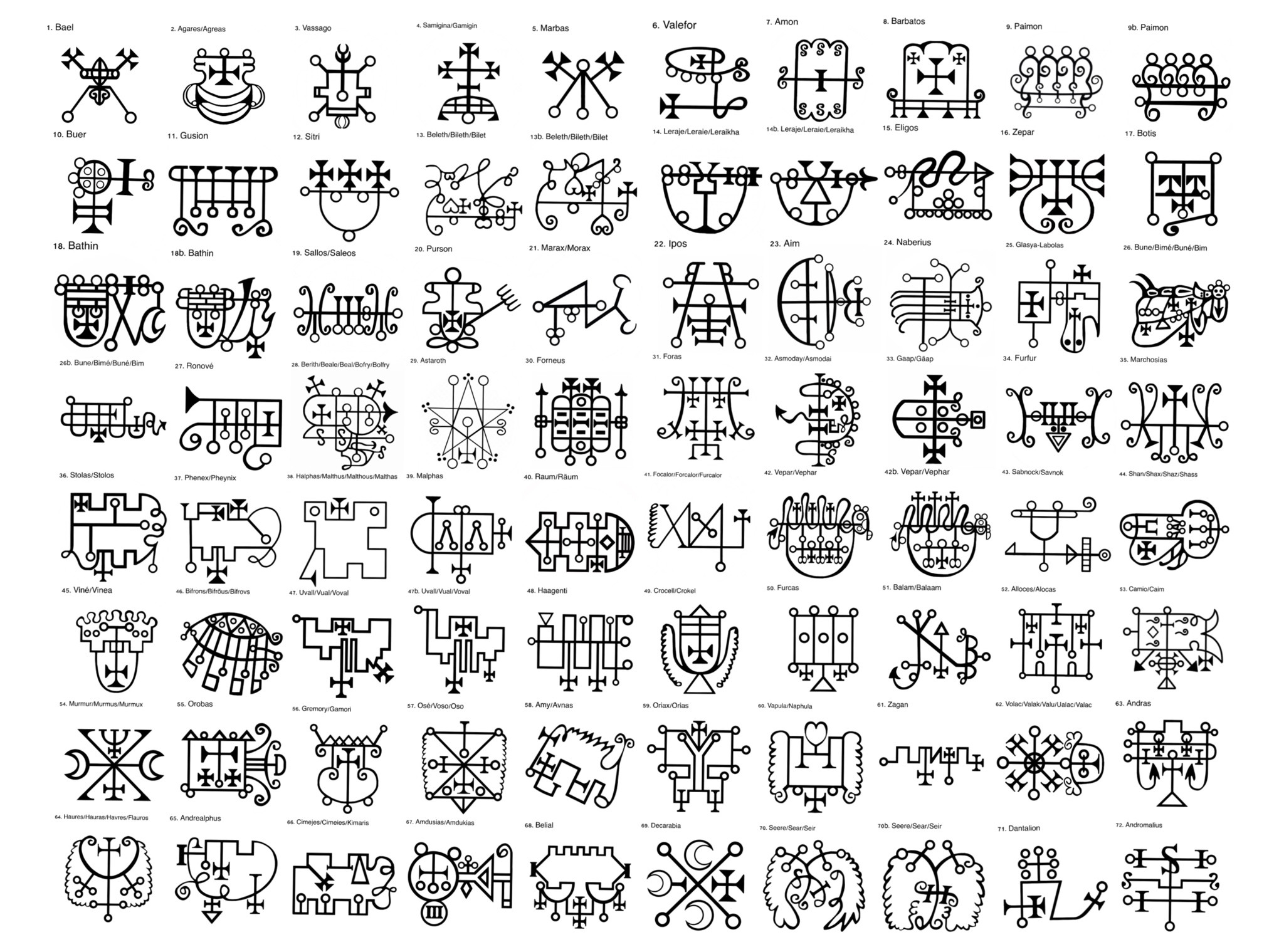

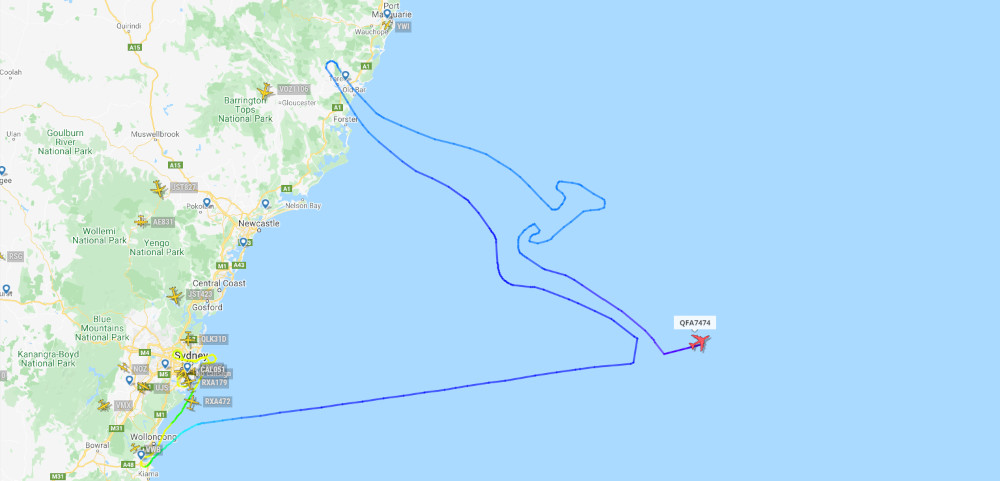

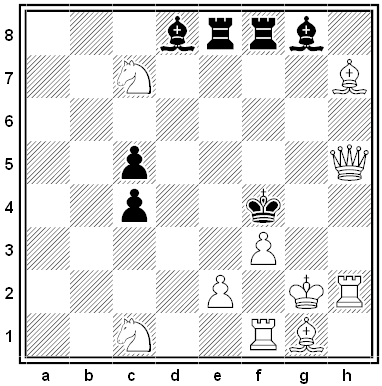

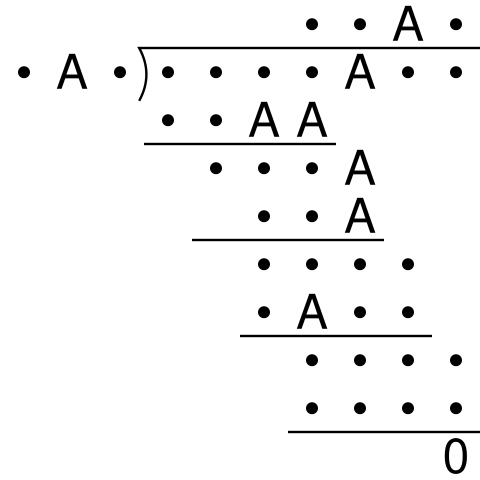

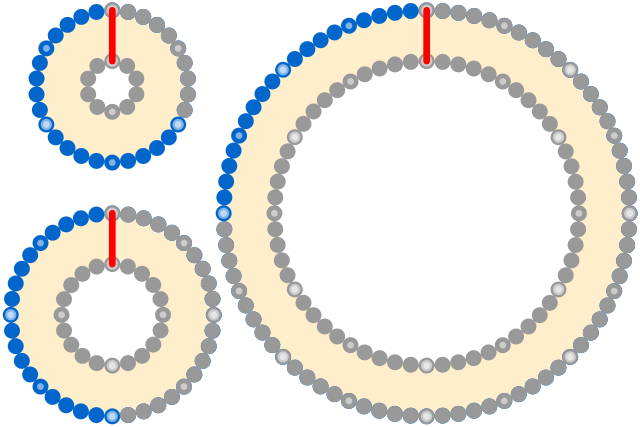

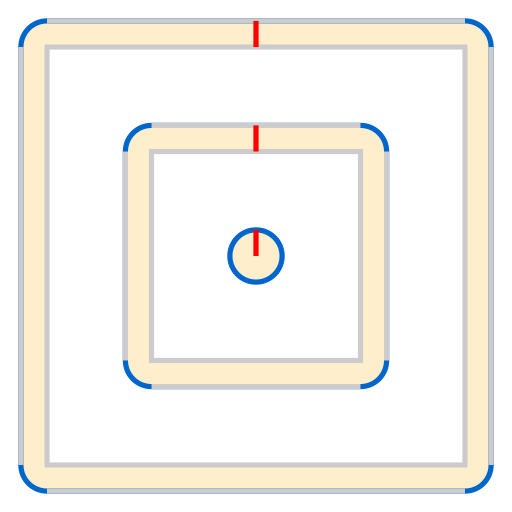

There were, to begin with, about 12,000 pages of typescript comprising the amended ‘biography’ of Kirk Allen. This was divided into some 200 chapters and read like fiction. Appended to these pages were approximately 2,000 more of notes in Kirk’s handwriting, containing corrections necessitated by his more recent ‘researches,’ and a huge bundle of scraps and jottings on envelopes, receipted bills, laundry slips. There also were a glossary of names and terms that ran to more than 100 pages; 82 full-color maps carefully drawn to scale, 23 of planetary bodies in four projections, 31 of land masses on these planets, 14 labeled ‘Kirk Allen’s Expedition to –,’ the remainder of cities on the various planets; 161 architectural sketches and elevations, all carefully scaled and annotated; 12 genealogical tables; an 18-page description of the galactic system in which Kirk Allen’s home planet was contained, with four astronomical charts, one for each of the seasons, and nine star-maps of the skies from observatories on other planets in the system; a 200-page history of the empire Kirk Allen ruled, with a three-page table of dates and names of battles or outstanding historical events; a series of 44 folders containing from 2 to 20 pages apiece, each dealing with some aspect — social, economic, or scientific — of the planet over which Kirk Allen ruled. Finally, there were 306 drawings of people, animals, plants, insects, weapons, utensils, machines, articles of clothing, vehicles, instruments, and furniture.

To free Allen from his delusion, Lindner eventually entered it himself, validating the fantasy and repeating Allen’s ideas in the same language. This worked: After some time Allen confessed that he no longer felt that his alternate identity was real. Lindner published his account of the therapy in two articles in Harper’s Magazine in 1955 and elaborated them in his 1955 memoir The Fifty-Minute Hour. Allen’s identity remains unknown, but there’s some speculation that he was Paul Linebarger — who himself wrote science fiction under the name Cordwainer Smith.