I will, as briefly as I may,

The sweets of liberty display.

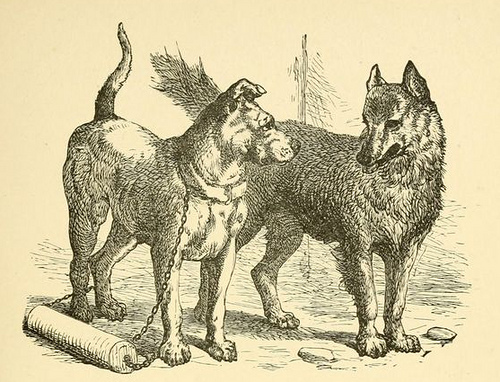

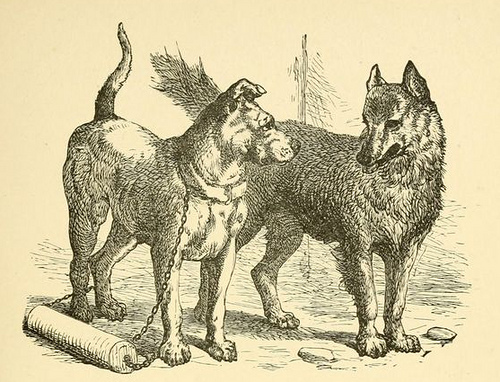

A Wolf half famish’d, chanced to see

A Dog, as fat as dog could be:

For one day meeting on the road,

They mutual compliments bestowed:

“Prithee,” says Isgrim, faint and weak,

“How came you so well fed and sleek?

I starve, though stronger of the two.”

“It will be just as well with you,”

The Dog quite cool and frank replied,

“If with my master you’ll abide.”

“For what?” “Why merely to attend,

And from night thieves the door defend.”

“I gladly will accept the post,

What! shall I bear with snow and frost

And all this rough inclement plight,

Rather than have a home at night,

And feed on plenty at my ease?”

“Come, then, with me” — the Wolf agrees.

But as they went the mark he found,

Where the Dog’s collar had been bound:

“What’s this, my friend?” “Why, nothing.”

“Nay, Be more explicit, sir, I pray.”

“I’m somewhat fierce and apt to bite,

Therefore they hold me pretty tight,

That in the day-time I may sleep,

And night by night my vigils keep.

At evening tide they let me out,

And then I freely walk about:

Bread comes without a care of mine.

I from my master’s table dine;

The servants throw me many a scrap,

With choice of pot-liquor to lap;

So, I’ve my bellyful, you find.”

“But can you go where you’ve a mind?”

“Not always, to be flat and plain.”

“Then, Dog, enjoy your post again,

For to remain this servile thing,

Old Isgrim would not be a king.”

— Phaedrus