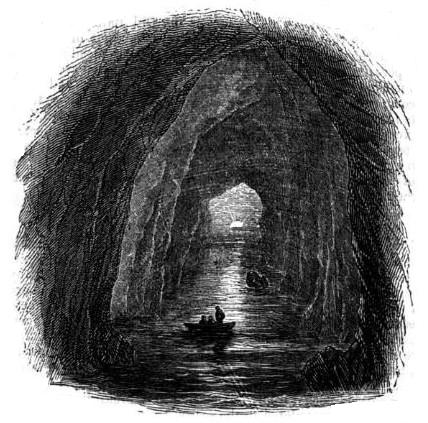

The above is a sketch of a cave which well deserves a place among our collection of Wonders. It is called Port Coon Cave, and is in the line of rocks near the Giants’ Causeway. It may be visited either by sea or by land. Boats may row into it to the distance of a hundred yards or more, but the swell is sometimes dangerous; and although the land entrance to the cave is slippery, and a fair proportion of climbing is necessary to achieve the object, still the magnificence of the excavation, its length, and the formation of the interior, would repay greater exertion; the stones of which the roof and sides are composed, and which are of a rounded form, and embedded, as it were, in a basaltic paste, are formed of concentric spheres resembling the coats of an onion; the innermost recess has been compared to the side aisle of a Gothic cathedral; the walls are most painfully slimy to the touch; the discharge of a loaded gun reverberates amid the rolling of the billows, so as to thunder a most awful effect; and the notes of a bugle, we are told, produced delicious echoes.

— Edmund Fillingham King, Ten Thousand Wonderful Things, 1860