Arrange the digits 0-9 into a 10-digit number such that the leftmost n digits comprise a number divisible by n. For example, if the number is ABCDEFGHIJ, the number ABC must be divisible by 3, ABCDE must be divisible by 5, and so on.

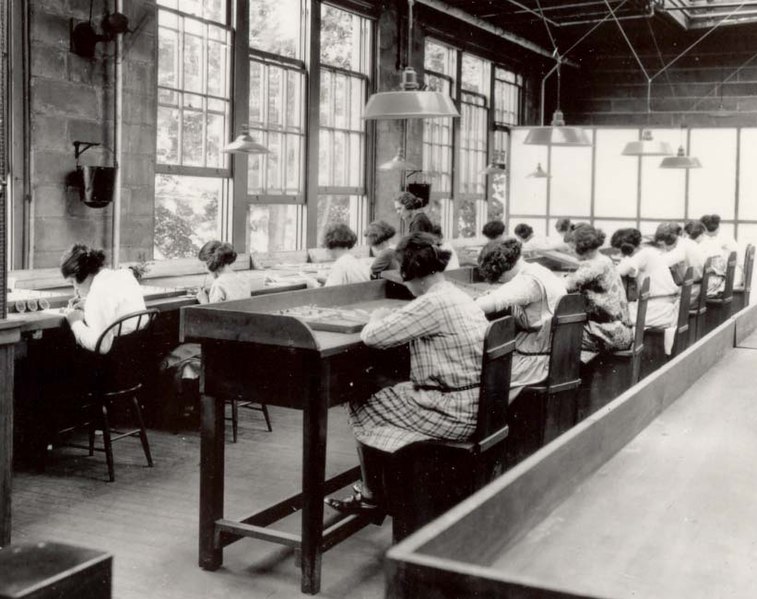

Podcast Episode 358: The Radium Girls

In 1917, a New Jersey company began hiring young women to paint luminous marks on the faces of watches and clocks. As time went on, they began to exhibit alarming symptoms, and a struggle ensued to establish the cause. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of the Radium Girls, a landmark case in labor safety.

We’ll also consider some resurrected yeast and puzzle over a posthumous journey.

“Forgotten Words Are Mighty Hard to Rhyme”

Quoth I to me, “A chant royal I’ll dite,

With much ado of words long laid away,

And make windsuckers of the bards who cite

The sloomy phrases of the present day.

My song, though it encompass but a page,

Will man illume from April bud till snow —

A song all merry-sorry, con and pro.”

(I would have pulled it off, too, given time,

Except for one small catch that didn’t show:

Forgotten words are mighty hard to rhyme.)

Ah, hadavist, in younghede, when from night

There dawned abluscent some fair morn in May

(The word for dawning, ‘sparrowfart,’ won’t quite

Work in here) — hadavist, I say,

That I would ever by stoopgallant age

Be shabbed, adushed, pitchkettled, suggiled so,

I’d not have been so redmod! Could I know? —

One scantling piece of outwit’s all that I’m

Still sure of, after all this catch-and-throw:

Forgotten words are mighty hard to rhyme.

In younghede ne’er a thrip gave I for blight

Of cark or ribble; I was ycore, gay;

I matched boonfellows hum for hum, each wight

By eelpots aimcried, till we’d swerve and sway,

Turngiddy. Blashy ale could not assuage

My thirst, nor kill-priest, even. No Lothario

Could overpass me on Poplolly Row.

A fairhead who eyebit me in my prime

Soon shared my donge. (The meaning’s clear, although

Forgotten words are mighty hard to rhyme.)

Fair draggle-tails once spurred my appetite;

Then walking morts and drossels shared my play.

Bedswerver, smellsmock, housebreak was I hight —

Poop-noddy at poop-noddy. Now I pray

That other fonkins reach safe anchorage —

Find bellibone, straight-fingered, to bestow

True love, till truehead in their own hearts grow.

Still, umbecasting friends who scrowward climb,

I’m swerked by mubblefubbles. Wit grows slow;

Forgotten words are mighty hard to rhyme.

Dim on the wong at cockshut falls the light;

Birds’ sleepy croodles cease. Not long to stay …

Once nesh as open-tide, I now affright;

I’m lennow, spittle-ready — samdead clay,

One clutched bell-penny left of all my wage.

Acclumsied now, I dare no more the scrow,

But look downsteepy to the Pit below.

Ah, hadavist! … Yet silly is the chime;

Such squiddle is no longer apropos.

Forgotten words are mighty hard to rhyme.

— Willard R. Espy

Blood Brothers

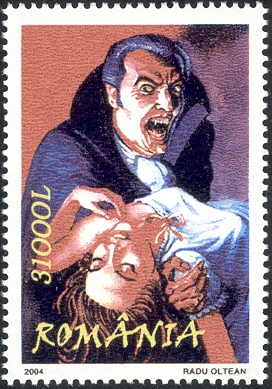

In 1900, three years after Bram Stoker published Dracula, a variant of the story was serialized in the Reykjavík newspaper Fjallkonan. When Makt Myrkranna (Powers of Darkness) was published in book form in 1901, the volume credited Valdimar Ásmundsson, the newspaper’s editor, as its translator.

The origins of the Icelandic version of Stoker’s tale remained a puzzle for more than a century. In 2017 it came to light that it had been adapted from an earlier newspaper serialization in Swedish, titled Mörkrets makter.

In fact it appears there were two Swedish variants, one of which seems to have served as the basis for the Icelandic version. All three of these differ significantly from Stoker’s familiar novel, though they include all the main characters.

How all this came about is still the subject of intense research. But despite their mystery, in some eyes the Nordic variants are superior to Stoker’s original. Dutch literary researcher Hans Corneel de Roos wrote, “Although Dracula received positive reviews in most newspapers of the day … the original novel can be tedious and meandering … Powers of Darkness, by contrast, is written in a concise, punchy style; each scene adds to the progress of the plot.”

“Epitaph on Fop, A Dog Belonging to Lady Throckmorton”

Though once a puppy, and though Fop by name,

Here moulders one, whose bones some honour claim;

No sycophant, although of spaniel race,

And though no hound, a martyr to the chase.

Ye squirrels, rabbits, leverets, rejoice!

Your haunts no longer echo to his voice;

This record of his fate exulting view,

He died, worn out with vain pursuit of you.

“Yes” — the indignant shade of Fop replies —

“And worn with vain pursuit man also dies.”

— William Cowper, 1792

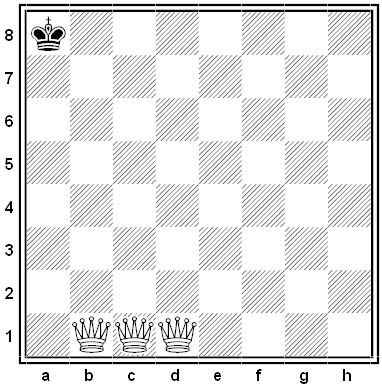

Black and White

From Henry Dudeney’s Perplexities column, Strand, March 1911:

“Here is a pretty little chess puzzle, made some years ago by Mr. F. S. Ensor. White has to checkmate the Black king without ever moving a queen off the bottom row, on which they at present stand. It is not difficult. As the White king is not needed in this puzzle, His Majesty’s attendance is dispensed with. His three wives can dispose of the enemy without assistance — in seven moves.”

“A Match Puzzle”

This puzzle, by T.E. Maw of the Luton Public Library, appeared in the Strand in April 1911:

“Take fifteen matches and place them as shown in the diagram, then take away three, change the position of one, and the result will be the word showing what matches are made of.”

Sorcery

New Zealand has a wizard. Born in London in 1932, Ian Channell invented the role at the University of New South Wales when a teaching fellowship ended. “I’ve invented a wizard out of nowhere,” he told CNN. “There were no wizards when I arrived in the world, except in books.”

After a stint as an unpaid “cosmologer, living work of art, and shaman” at Melbourne University, he settled in Christchurch in the 1970s and began speaking on a ladder in Cathedral Square. The city council opposed him at first, but his profile rose. In 1982, the New Zealand Art Gallery Directors Association declared him a living work of art; in 1988 he performed a rain dance in the town of Waimate to break a drought; and in 1990 Prime Minister Mike Moore invited him to become Wizard of New Zealand (“No doubt there will be implications in the area of spells, blessings, curses, and other supernatural matters that are beyond the competence of mere Prime Ministers”).

In 1998 the Christchurch City Council engaged him to “provide acts of wizardry and other wizard-like-services as part of promotional work for the city of Christchurch” for 16,000 New Zealand dollars a year. He helps to promote local events and tourism and welcome dignitaries and delegations to the city. In 2009 he received the Queen’s Service Medal, one of the country’s highest honors (“I couldn’t believe it, I thought it would never happen”).

Now 88 years old, Channell is cultivating an apprentice, Ari Freeman, who may take over when he steps down. “I want the wizard phenomenon to continue,” Freeman said, “and I will totally fulfill that role.”

Exam Week

A problem submitted by the United States and shortlisted for the 16th International Mathematical Olympiad, Erfurt-Berlin, July 1974:

Alice, Betty, and Carol took the same series of examinations. There was one grade of A, one grade of B, and one grade of C for each examination, where A, B, C are different positive integers. The final test scores were

Alice: 20

Betty: 10

Carol: 9If Betty placed first in the arithmetic examination, who placed second in the spelling examination?

Benedetti’s Puzzle

This is interesting: In 1585, Italian mathematician Giovanni Battista Benedetti devised a piece of music in which a precise application of the tuning mathematics causes the pitch to creep upward.

Avoiding this phenomenon requires an adjustment — a compromise to the dream of mathematically pure music.