elozable

adj. amenable to flattery

In Other News

March 15, 1761, Tregoney, in Cornwall. As some tinners were lately employed on a new mine, one of them accidentally struck his pick-axe on a stone. The earth being removed, a coffin was found. On removing the lid they discovered a skeleton of a man of gigantic size, which, on the admission of the air, mouldered into dust. One entire tooth remained whole, which was two inches and a half long, and thick in proportion. The length of the coffin was eleven feet three inches, and depth three feet nine inches.

— Annual Register, 1761

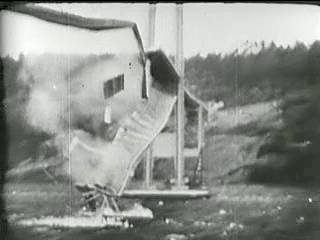

Bridge to Nowhere

On Nov. 7, 1940, photographer Leonard Coatsworth was halfway across Washington’s Tacoma Narrows Bridge when he felt it move strangely:

“Just as I drove past the towers, the bridge began to sway violently from side to side. Before I realized it, the tilt became so violent that I lost control of the car. … I jammed on the brakes and got out, only to be thrown onto my face against the curb… Around me I could hear concrete cracking. … The car itself began to slide from side to side of the roadway.”

Gripping the curb, he crawled 500 yards back toward the toll plaza, turned and watched his car plunge into the Narrows. With it went his daughter’s dog, Tubby, who was too terrified to jump out.

The bridge had been competently designed, with supports by Golden Gate designer Leon Moisseiff, but no one had counted on its twisting and buckling in the wind.

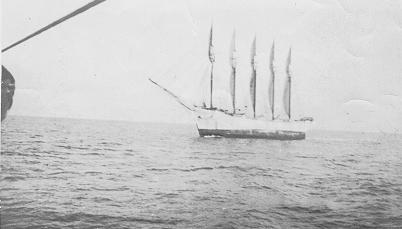

A Nautical Mystery

On Jan. 31, 1921, the five-masted commercial schooner Carroll A. Deering was found aground in North Carolina. The ship’s log, navigation equipment and lifeboats were missing, as were the crew’s personal effects. She had last been sighted by a lightship at Cape Lookout, whose captain had spoken with a thin man with reddish hair and a foreign accent — decidedly not the Deering‘s captain. The lightship also noted that the crew seemed to be “milling around” on the Deering‘s foredeck, where they were usually not allowed.

But that’s all anyone knows, really. The crew’s disappearance remains unexplained to this day. Was it piracy? Mutiny? A commandeering by Russian communists? Without evidence, it remains a mystery.

Beats Me

The Wolfsegg Iron is a lump of iron found inside a block of coal at a mine in the Austrian village of Wolfsegg. The scientific journal Nature describes it as “almost a cube” with a “deep incision” running around it. It weighs about 1.7 pounds.

It’s not at all clear where it can have come from. A meteorite would not have such an artificially cubical shape, and prehistoric civilizations should not have had the technology to make such a thing.

After a thorough examination in 1966, researchers at Vienna’s Natural History Museum concluded that the block is simply man-made cast iron, perhaps used as ballast in primitive mining machinery. But no other such blocks have ever been found.

Suburban Physics

You’re driving a car. The windows are closed. In the back seat is a kid holding a helium balloon.

You turn right. You and the kid sway to the left. What does the balloon do?

Math Notes

25 × 92 = 2592

Lost and Found

In 1940, British colonial officer Gerald Gallagher found a human skeleton and a sextant box under a tree on Gardner Island, a coral atoll in the western Pacific. Colonial authorities took detailed measurements, and in 1998 forensic anthropologists judged that the skeleton had belonged to a “tall white female of northern European ancestry.”

It may have been Amelia Earhart.

The Loneliest Number

When Washington’s power elite convene for the president’s annual State of the Union address, there’s always a cabinet member missing:

- 2007: Alberto Gonzales, attorney general

- 2006: Jim Nicholson, secretary of veterans affairs

- 2005: Donald Evans, secretary of commerce

- 2004: Donald Evans, secretary of commerce

- 2003: John Ashcroft, attorney general

- 2002: Gale Norton, secretary of the interior

- 2001: Anthony Principi, secretary of veterans affairs

- 2000: Bill Richardson, secretary of energy

That member stays at a remote location in case some catastrophe strikes the Capitol.

He’s called the designated survivor.

“Astonishing Natural Phenomenon”

On the 27th of August, 1814, while the Majestic, Capt. Hayes, was cruising off Boston, a strange figure was perceived in the eastern horizon, about two o’clock in the morning; which, as the sun arose, gradually became more distinguishable, and, at length, assumed the perfect appearance of a man, dressed in a short jacket and half boots, with a staff in his hand, at the top of which was a colour hanging over his head, marked with two lines, perpendicularly drawn at equal distances, and strongly resembling the French flag. The figure continued visible as long as the rays of the sun would permit it to be looked at. On the 28th the figure displayed itself in the same posture, but rather broken. On the following morning, it seemed entirely disjointed, and faded into shadow, until, at last, nothing more could be seen than three marks on the sun’s disk. — Captain Hayes, his officers, and about 200 of the crew, witnessed the spectacle, both with the naked eye and through glasses. In superstitious times, such a phenomenon would have been construed into a providential warning or ominous token of some unexpected event; in this enlightened age, however, it may be easily accounted for by the reflective power of the atmosphere, which is well known to be wonderful. Most probably the figure represented was some one ashore, or on the deck of the Majestic.

— Courier, June 13, 1815