In 1938, Stefan Banach proved that it’s always possible to slice a ham and cheese sandwich in half such that each half contains the same amount of bread, cheese, and ham.

It’s called the ham sandwich theorem.

In 1938, Stefan Banach proved that it’s always possible to slice a ham and cheese sandwich in half such that each half contains the same amount of bread, cheese, and ham.

It’s called the ham sandwich theorem.

When Scogin was banished out of France, he filled his shooes full of French earth, and came into England, and went into the king’s court, and as soone as he came to the court, the king said to him: I did charge thee that thou shouldest never tread upon my ground of England. It is true, said Scogin, and no more I doe. What! traytor, said the king, whose ground is that thou standest on now? Scogin said: I stand upon the French king’s ground, and that you shall see; and first he put off the one shooe, and it was full of earth. Then said Scogin: this earth I brought out of France. Then said the king: I charge thee never to looke me more in the face.

— Scoggin’s Jests, 1626

After losing a bet in April 1864, shopkeeper Reuel Gridley carried a 50-pound sack of flour through the little town of Austin, Nev. In a saloon afterward, someone proposed selling the flour at auction for the benefit of wounded Union soldiers. The suggestion was adopted on the spot, and the winning bid, $250, came from a local mill worker.

When Gridley asked where to deliver the sack, the man said, “Nowhere — sell it again.”

Thus was born a unique enterprise: Three hundred people paid a total of $8,000 for the same sack of flour that day, and soon Gridley went on tour through other Nevada mining towns, raising tens of thousands of dollars by selling it repeatedly. By the war’s end he had extended the tour through California, New York, and St. Louis and raised $150,000, a fortune for the time. Mark Twain wrote, “This is probably the only instance on record where common family flour brought three thousand dollars a pound in the public market.”

The Stanley Cup travels more than 100,000 miles a year, making it the best-traveled championship trophy in the world. Misadventures:

Plus untold numbers have slept with it and urinated in it — one hopes in that order.

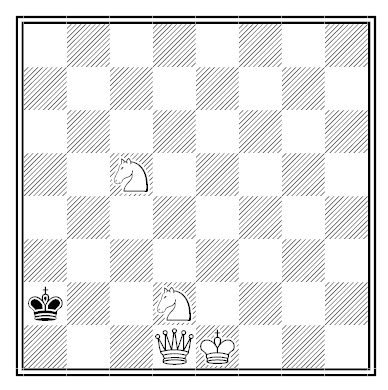

By W. Bone. White to move and mate in four.

The catch: He must mate with the queen — and she’s glued to the board.

In the year 1796, died at Wordley Workhouse, Berks, Mary Pitts, aged 70; on being accused of having rummaged the box of another pauper, she wished God might strike her dead if she had; and instantly expired.

— Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum, 1803

27 × 81 = 2187

35 × 41 = 1435

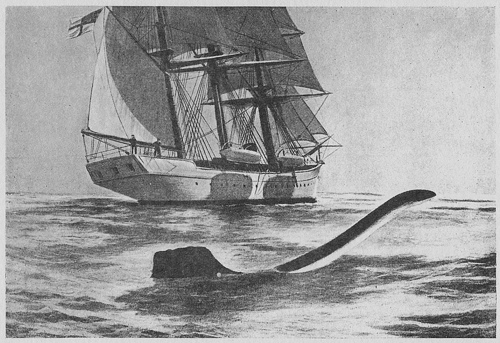

On Dec. 7, 1905, British naturalists J. Nicoll and E.G.B. Meade-Waldo spotted “a creature of most extraordinary form and proportions” during a research cruise off the coast of Brazil. Nicoll described a head “shaped somewhat like that of a turtle” above a 6-foot “eel-like” neck that “lashed up the water with a curious wriggling movement.” Below the water “we could indistinctly see a very large brownish-black patch, but could not make out the shape of the creature.”

They later spied it doing about 8.5 knots, slightly faster than the ship: “From the commotion in the water it looked as if a submarine was going along just below the surface.” The witnesses insisted it was not a whale, though Nicoll felt it was a mammal. That’s all we know.

A curious episode from Goethe’s autobiography:

I rode along the footpath towards Drusenheim, and here one of the most singular forebodings took possession of me. I saw, not with the eyes of the body, but with those of the mind, my own figure coming towards me, on horseback, and on the same road, attired in a dress which I had never worn ; — it was pike-grey with some gold about it. But as I shook myself out of this dream, the figure had entirely disappeared. It is strange, however, that eight years afterwards, I found myself on that very road, on my way to pay one more visit to Frederica, wearing the dress of which I had dreamed, and that, not from choice, but by accident.

“Whatever one may think on such matters in general,” he wrote, “in this instance my strange illusion helped to calm me in this farewell hour.” So there’s that.

As a teenager, George Washington copied out “110 rules of civility and decent behavior in company and conversation,” probably as an exercise in penmanship. Samples:

Washington didn’t compose these — they were originally devised by French Jesuits in 1595 — but both Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin later wrote their own rules of good conduct.