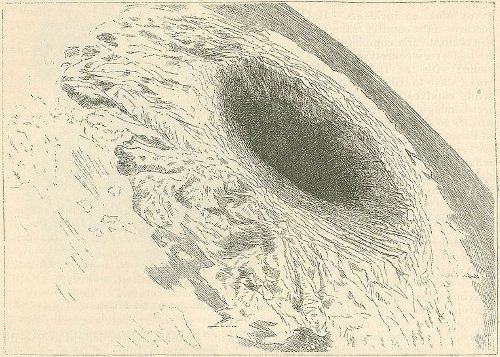

On April 10, 1818, John Cleves Symmes Jr. of Ohio issued the following challenge:

To All The World. — I declare the earth to be hollow and habitable within; containing a number of concentric spheres, one within the other, and that their poles are open twelve or sixteen degrees. I pledge my life in support of this truth, and am ready to explore the concave, if the world will support and aid me in the undertaking.

I ask one hundred brave companions, well equipped, to start from Siberia, in autumn, with reindeer and sledges, on the ice of the Frozen Sea; I engage we find a warm country and rich land, stocked with thrifty vegetables and animals, if not men, on reaching about sixty-nine miles northward of latitude 82; we will return in the succeeding spring.

Kentucky senator (and future vice president) Richard M. Johnson proposed that Congress fund two vessels for the expedition, but Congress voted this down. But we have an account of the voyage anyway: An anonymous hoaxer published Symzonia: A Voyage of Discovery under Symmes’ name in 1820.