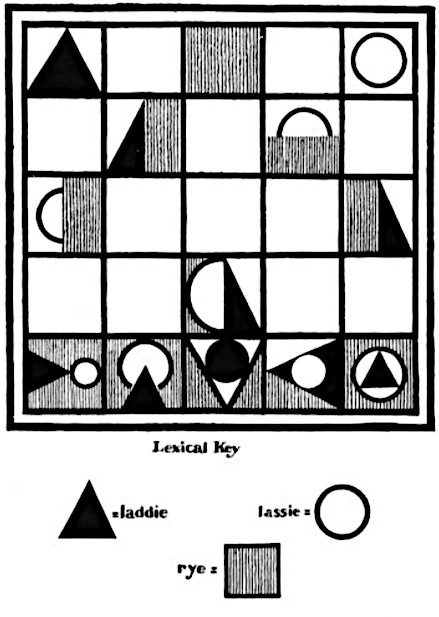

A concrete poem by John Furnival, 1965:

A concrete poem by John Furnival, 1965:

Devised by English orthographer Christopher Upward, Cut Spelling seeks to reform English by eliminating and substituting letters to better match the spoken word:

Wen readrs first se Cut Spelng, as in this sentnce, they ofn hesitate slytly, but then quikly becom acustmd to th shortnd words and soon find text in Cut Spelng as esy to read as traditional orthografy, but it is th riter ho realy apreciates th advantajs of Cut Spelng, as many of th most trublsm uncertntis hav been elimnated.

Words in this scheme are 8 to 15 percent shorter than their standard spellings, and the rules are more systematic, arguably making them easier to learn for both newcomers and established readers. The plan was promoted for a time by the Simplified Spelling Society but, like so many other reform proposals, never achieved wide acceptance.

From the diary of Richard Burton, Oct. 16, 1968:

Stanley Donen told me a funny one about Osgood Perkins. It seems that Perkins was in a long-running melodrama in which he had to kill a character in the last act with a letter opener, stiletto type. One day the props man forgot to put the knife on the table and there was no other instrument around. So instead of throttling his murderee as anybody in his right senses would have done he kicked him smartly up his arse, the fellow fell down and feigned death, and Perkins raked the house with his eyes and said: ‘Fortunately the toe of my boot was poisoned.’

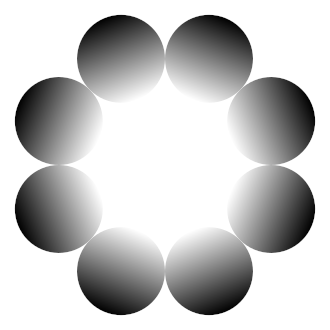

The center of this figure appears unusually bright, but it’s no different than the rest of the page.

Interestingly, the pupils of both primates and rats constrict when viewing the figure, evidence of similarity in perception between humans and animals.

A little boy spent his first day at school. ‘What did you learn?’ was his aunt’s question. ‘Didn’t learn nothing.’ ‘Well, what did you do?’ ‘Didn’t do nothing. There was a woman wanting to know how to spell “cat,” and I told her.’

— John Scott, The Puzzle King, 1899

The 12-year-old Winston Churchill found examinations “a great trial”: “I would have liked to have been examined in history, poetry and writing essays. … I should have liked to be asked to say what I knew. They always tried to ask what I did not know.”

This year’s GCHQ Christmas Challenge is now live. Devised by Government Communications Headquarters, the British intelligence agency, this year’s quiz presents seven puzzles for children aged 11-18. They’re designed to test a range of problem-solving skills, including creativity and intuitive reasoning.

Agency director Anne Keast-Butler said: “Puzzles are at the heart of GCHQ’s work to keep the country safe from hostile states, terrorists and criminals; challenging our teams to think creatively and analytically every day.”

This lugubrious statue stands in a niche in London’s Holland Park. It’s been there since the Formal Gardens were created in 1812, but it probably dates from at least the 16th century, which would make it one of the oldest complete outdoor statues in the city. No one knows who created it or the reason for its dour expression. It’s known as the Ancient Melancholy Man.

It’s featured on the cover of Van Morrison’s 1986 album No Guru, No Method, No Teacher.

(Thanks, Valérie.)

Draw a circle and choose 100,000 points at random in its interior. Is it always possible to draw a line through the circle such that 50,000 points lie on each side of it?

In the March 1992 newsletter of Australia’s Society of Editors, John Bangsund offered a rule that he called Muphry’s Law:

(a) if you write anything criticizing editing or proofreading, there will be a fault of some kind in what you have written;

(b) if an author thanks you in a book for your editing or proofreading, there will be mistakes in the book;

(c) the stronger the sentiment expressed in (a) and (b), the greater the fault;

(d) any book devoted to editing or style will be internally inconsistent.

In November 2003, the Canberra Editor noted, “Muphry’s Law also dictates that, if a mistake is as plain as the nose on your face, everyone can see it but you. Your readers will always notice errors in a title, in headings, in the first paragraph of anything, and in the top lines of a new page. These are the very places where authors, editors and proofreaders are most likely to make mistakes.”

Earlier, editor Joseph A. Umhoefer had observed that “Articles on writing are themselves badly written.” A correspondent wrote that Umhoefer “was probably the first to phrase it so publicly; however, many others must have thought of it long ago.”

In Arthur Ransome’s 1933 children’s novel Winter Holiday, Nancy Blackett, quarantined with mumps, sends a picture to her friends of a sledge being drawn by skating figures. Nancy is encouraging the group to pursue their plan to explore a frozen lake. The seven figures in the picture correspond to the seven children in the group. “But,” asks Peggy, “what did she put in the crowd for?”