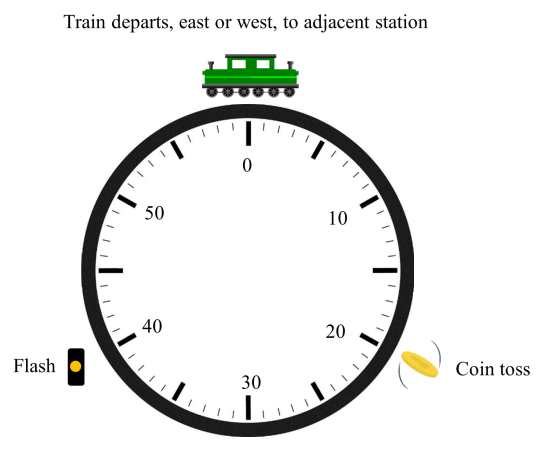

A train line extends infinitely far east and west. Stations are spaced a mile apart, and midway between each pair of stations is a signal light. There’s one train on the line, and it moves to an adjacent station at the top of each hour. Its choice (east or west) is determined by the engineer, who flips a coin 20 minutes after each hour. If the coin lands heads, the train’s next destination will be the station one mile east. If it lands tails, the train will next go to the station one mile west.

Forty minutes after each hour, one of the infinitely many signal lights will flash. The flash is visible all along the line. The identity of the flashing light is random, and it’s unrelated to the coin toss.

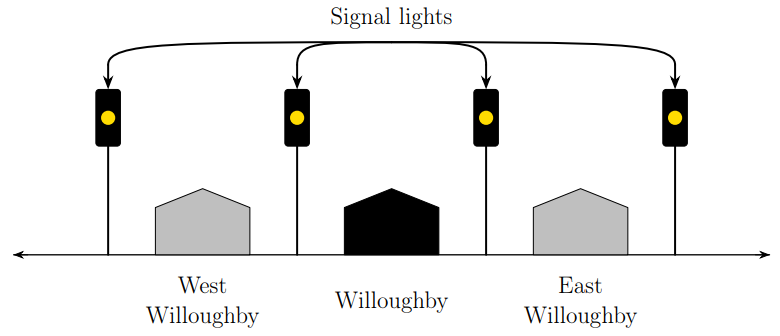

You wake up on this train while it’s stopped at a station. It’s 2:30 p.m., which means the engineer flipped his coin 10 minutes ago. The conductor tells you that the next destination is Willoughby. A map tells you that the Willoughby station is flanked by East Willoughby and West Willoughby, so you must be at one of these two stations, but you don’t know which one. Because these are the only two possibilities and there’s no reason for one to be more likely, you conclude that they’re equally probable.

Before the train departs at 3 p.m., is it possible to guess the outcome of the engineer’s coin toss at 2:20 p.m. with success probability greater than 1/2? El Camino College mathematician Leonard M. Wapner contends that it is. At 2:40 p.m. a signal light will flash. There’s a nonzero probability p that the light that flashes will be one of the two lights adjacent to the Willoughby station. If that happens, it will indicate with certainty the direction of Willoughby (east or west) from your current location. The chance that the flash doesn’t come from one of these two lights is 1 – p, and in that case the chance is 1/2 that it comes from the direction of Willoughby. Overall:

“So,” Wapner writes, “if the light flashes to your east, you would guess that the train will be departing to the east and that the engineer’s coin landed heads. If the light flashes to the west, you would guess that the train will depart to the west and that the engineer’s coin landed tails. You should expect your guess (east/heads or tails/west) to be successful more often than not.”

(He adds, “The Willoughby prediction scheme, though mathematically valid, is far too contrived for it to be achieved in actuality. But there being no mathematical contradictions, the door remains open to variations and applications.”)

(Leonard M. Wapner, “Beyond Chance: Predicting the Unpredictable,” Recreational Mathematics Magazine 12:21 [December 2025], 1-8.)