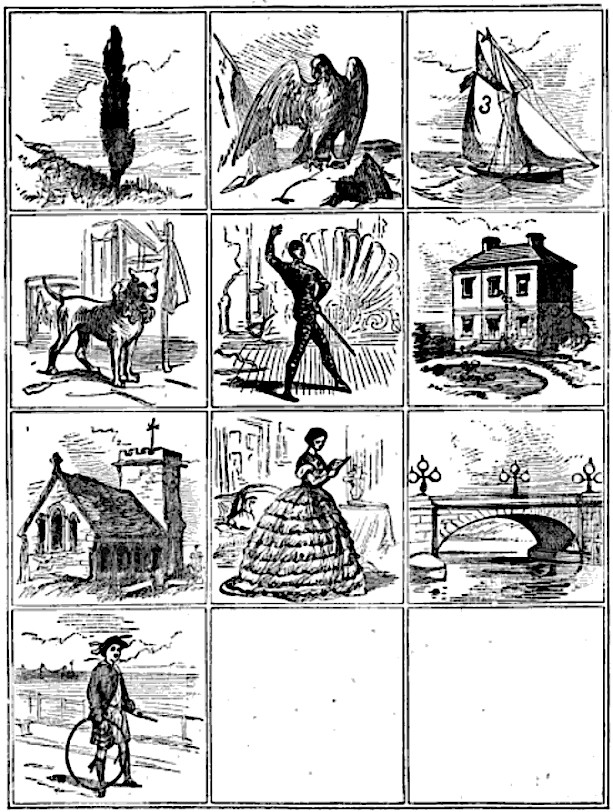

William Stokes’ Pictorial Multiplication Table of 1866 promised to teach multiplication facts to a child of average ability in less than half an hour. It did this by representing each digit with an object:

A TREE means 1, from one trunk springs.

A BIRD means 2, it has two wings.

A BOAT is 3, three sails are shown.

ANIMALS 4, four legs they own.

A MAN means 5, five fingers he.

A HOUSE means 6, six windows see.

A CHURCH means 7, not windows less.

A LADY 8, see eight-flounced dress.

A BRIDGE is 9, nine lamps are found.

A BOY means 0, see hoop so round.

Now each fact can be represented by a picture. Here’s the “twice” table:

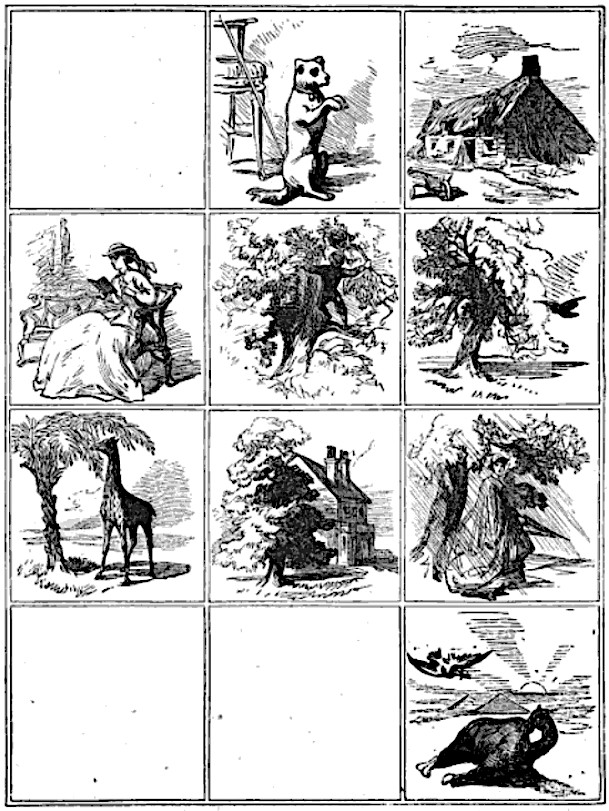

These are the products of 2 with the first 12 integers, in order. The second box, representing 2 × 2, depicts a dog, which is an ANIMAL with 4 legs, so 2 × 2 is 4. The sixth box, representing 2 × 6, depicts a TREE and a BIRD, so 2 × 6 = 12. And so on. The first box, which covers the fact that 2 × 1 = 2, is omitted because we’ve already mastered the fact that 1 × 2 = 2 (in the “once” table). The 10th and 11th boxes are blank because multiplication by 10 and 11 are considered so easy that no mnemonic is needed.

How can we remember the “twice” table itself? Stokes provides a verbal rhyme that sums it up:

Twice — Dog, Cot, Reader, Nest, and Bird flying;

Giraffe, Inn, Shower, and Camel dying.

In this way a student can master every fact up to 12 × 12 by memorizing 59 simple pictures (and 12 rhymes). How well this worked, and whether the images could be carried accurately in one’s head through a lifetime, is less clear.