Alexander William Kinglake suggested that all churches should bear the inscription IMPORTANT IF TRUE.

Alexander William Kinglake suggested that all churches should bear the inscription IMPORTANT IF TRUE.

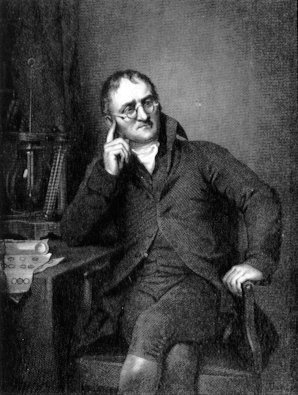

John Dalton was a tornado of English science, exploring atomic theory, meteorology, perception, and the physics of gases with equal avidity.

But he was a Quaker, and when in 1834 he was invited to be presented to William IV, the question arose whether he could properly appear in the scarlet robes of an Oxford doctor of laws, as the color was forbidden to him.

Dalton solved this neatly: He pointed out that he was color-blind. “You call it scarlet,” he said. “To me its color is that of nature — the color of green leaves.”

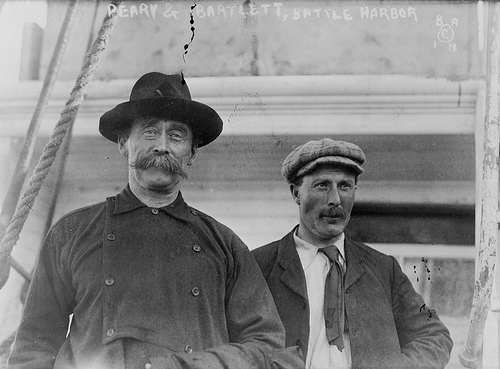

Robert Peary’s attempts to reach the North Pole raised a curious question for Jewish scholars: How should Jewish law, which normally assumes a 24-hour day, be interpreted in the land of the midnight sun?

Writing in New Era in 1905, J.D. Eisenstein asked, “Which is the seventh day, or Sabbath? and when is Yom Kippur to be observed around the North Pole, where the day and night are of about six months’ duration?”

If one reckoned by daylight, “As to Yom Kippur, it would be obviously impossible to prolong the fast till the closing prayer of Neilah. Besides, one would have to wait for the following Yom Kippur, 354 to 384 years, figuring a year for a day, according to the Jewish calendar.”

According to Eisenstein, one rabbi advised that observing Jews should not settle in high latitudes at all, to avoid the question. The problem has not been entirely settled even today — indeed, it’s been compounded, as Jewish astronauts can now orbit the earth and may one day colonize other worlds.

A young gentleman happened to sit at church in a pew adjoining one in which sat a young lady for whom he conceived a sudden and violent passion, and was desirous of entering into a courtship on the spot; but the place not favoring a formal declaration, the exigency of the case suggested the following plan: he politely handed his fair neighbor a Bible opened, with a pin stuck in the following text:

‘And now I beseech thee, lady, not as though I wrote a new commandment unto thee, but that which we had from the beginning, that we love one another.’

She returned it, pointing to the verse in Ruth:

‘Then she fell on her face, and bowed herself to the ground, and said unto him, Why have I found grace in thine eyes, seeing I am a stranger?’

He returned the book, pointing to the following:

‘Having many things to write unto you, I would not with paper and ink: but I trust to come unto you, and speak face to face, that our joy may be full.’

A marriage soon after resulted from this Biblical interview.

— Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867

Buzz Aldrin celebrated communion on the moon. From his 2009 book Magnificent Desolation:

So, during those first hours on the moon, before the planned eating and rest periods, I reached into my personal preference kit and pulled out the communion elements along with a three-by-five card on which I had written the words of Jesus: ‘I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in him, will bear much fruit; for you can do nothing without me.’ I poured a thimbleful of wine from a sealed plastic container into a small chalice, and waited for the wine to settle down as it swirled in the one-sixth Earth gravity of the moon. My comments to the world were inclusive: ‘I would like to request a few moments of silence … and to invite each person listening in, wherever and whomever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way.’ I silently read the Bible passage as I partook of the wafer and the wine, and offered a private prayer for the task at hand and the opportunity I had been given.

“Perhaps, if I had it to do over again, I would not choose to celebrate communion,” he wrote. “Although it was a deeply meaningful experience for me, it was a Christian sacrament, and we had come to the moon in the name of all mankind — be they Christians, Jews, Muslims, animists, agnostics, or atheists. But at the time I could think of no better way to acknowledge the enormity of the Apollo 11 experience that by giving thanks to God.”

In his Notebooks, Samuel Butler tells a story of Herbert Clarke’s 10-year-old son:

His mother had put him to bed and, as he was supposed to have a cold, he was to say his prayers in bed. He said them, yawned and said, ‘The real question is whether there is a God or no,’ on which he instantly fell into a sweet and profound sleep which forbade all further discussion.

Elsewhere Butler wrote, “What is faith but a kind of betting or speculation after all? It should be, ‘I bet that my Redeemer liveth.'”

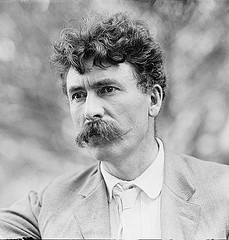

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) loved nature and loved God — so in a 1907 book he tried to prove that animals follow the 10 commandments:

Actually, he runs out of gas here — Seton was unable to convince even himself that animals avoid making graven images, swearing, or working on Sunday. So he concludes The Natural History of the Ten Commandments by deciding that “Man is concerned with all” the commandments, “the animals only with the last six.”

The Gospel of Luke contains a parable about a rich man and a beggar. Both men die, and the rich man is consigned to hell while the beggar is received into the bosom of Abraham. The rich man pleads for mercy, but Abraham tells him that in his lifetime he received good things and the beggar evil things: “now he is comforted and thou art tormented.” The rich man then begs that his brothers be warned of what lies in store for them, but Abraham rejects this plea as well, saying, “If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded though one rose from the dead.”

Now, writes E.V. Milner:

Suppose … that this last request of Dives had been granted; suppose, in fact, that some means were found to convince the living, whether rich men or beggars, that ‘justice would be done’ in a future life, then, it seems to me, an interesting paradox would emerge. For if I knew that the unhappiness which I suffer in this world would be recompensed by eternal bliss in the next world, then I should be happy in this world. But being happy in this world I should fail to qualify, so to speak, for happiness in the next world. Therefore, if there were such a recompense awaiting me, its existence would seem to entail that I should at least be not wholly convinced of its existence.

“Put epigrammatically, it would appear that the proposition ‘Justice will be done’ can only be true for one who believes it to be false. For one who believes it to be true justice is being done already.”

Kurt Gödel composed an ontological proof of God’s existence:

Axiom 1. A property is positive if and only if its negation is negative.

Axiom 2. A property is positive if it necessarily contains a positive property.

Theorem 1. A positive property is logically consistent (that is,

possibly it has an existence).

Definition. Something is God-like if and only if it possesses all positive properties.

Axiom 3. Being God-like is a positive property.

Axiom 4. Being a positive property is logical and hence necessary.

Definition. A property P is the essence of x if and only if x has the property P and P is necessarily minimal.

Theorem 2. If x is God-like, then being God-like is the essence of x.

Definition. x necessarily exists if it has an essential property.

Axiom 5. Being necessarily existent is God-like.

Theorem 3. Necessarily there is some x such that x is God-like.

“I am convinced of the afterlife, independent of theology,” he once wrote. “If the world is rationally constructed, there must be an afterlife.”