Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer, favored a “theory of ruin value” in which German buildings would collapse into aesthetically pleasing ruins, like those of classical antiquity. “I want German buildings to be viewed in a thousand years as we view Greece and Rome,” he said.

Using special materials and applying statistical principles, Speer claimed to have created structures that in 1,000 years would resemble Roman ruins. “The ages-old stone buildings of the Egyptians and the Romans still stand today as powerful architectural proofs of the past of great nations, buildings which are often ruins only because man’s lust for destruction has made them such,” he wrote.

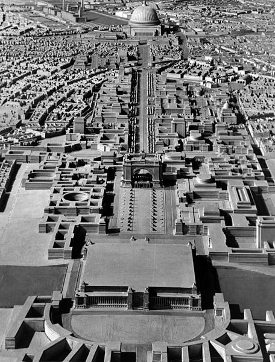

Hitler liked to say that the purpose of his building was to transmit his time and its spirit to posterity. Ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture, he remarked. What then remained of the emperors of the Roman Empire? What would still give evidence of them today, if not their buildings […] So, today the buildings of the Roman Empire could enable Mussolini to refer to the heroic spirit of Rome when he wanted to inspire his people with the idea of a modern imperium. Our buildings must also speak to the conscience of future generations of Germans.

Hitler endorsed the idea, favoring the use of durable materials such as granite to reflect his soaring ambitions. “As capital of the world,” he said, “Berlin will be comparable only to ancient Egypt, Babylon, or Rome!” Ironically, this came true: When ancient Rome collapsed, its greatest buildings were pillaged for building materials, and when the Russians demolished Speer’s grandiose Chancellery in 1947, its marble was reused to build a metro station.