Your friends probably have more friends than you do.

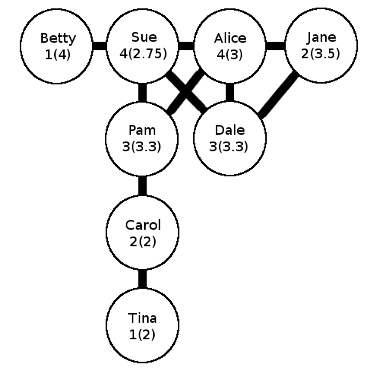

The diagram above shows friendships among eight high school girls. The first number in each circle is the girl’s number of friends; the second is the mean number of friends that her friends have. Only Sue and Alice have more friends than their friends do on average, but their popularity, by its very nature, will impress an inordinate number of people, leaving more feeling inadequate by comparison.

“Those with 40 friends show up in each of 40 individual friendship networks and thus can make 40 people feel relatively deprived,” writes SUNY sociologist Scott Feld, “while those with only one friend show up in only one friendship network and can make only that one person feel relatively advantaged.” In general, he finds, in a given network the mean number of friends of friends is always greater than the mean number of friends of individuals. But understanding this phenomenon “should help people to understand that their position is relatively much better than their personal experiences have led them to believe.”

The same phenomenon leads college students to feel that the mean class size is larger than it really is, and all of us to experience restaurants, parks, and beaches as more crowded than they really are. A highway impresses thousands with its congestion at rush hour, but few with its emptiness at midnight. So we tend to think of it as busier than it really is.

(Scott L. Feld, “Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do,” American Journal of Sociology, 96:6, 1464-1477)