English was Joseph Conrad’s third language. Born in Poland, he learned French as a child but heard no English until he went to sea as a teenager. In 1874 he had just rowed a dinghy alongside an English cargo steamer at Marseilles when a deck hand threw him a rope and called, “Look out there.” “For the very first time in my life, I heard myself addressed in English — the speech of my secret choice, of my future, of long friendships of the deepest affections, of hours of toil and hours of ease, and of solitary hours too, of books read, of thoughts pursued, of remembered emotions — of my very dreams!”

His captivation with the language, he would later say, was “too mysterious to explain,” “a subtle and unforeseen accord of my emotional nature with its genius.” He made his way to England and began to puzzle out newspaper articles with help from a local boat builder. “I began to think in English long before I mastered, I won’t say the style (I haven’t done that yet), but the mere uttered speech,” he wrote to Hugh Walpole in 1918. “You may take it from me that if I had not known English I wouldn’t have written a line for print in my life.”

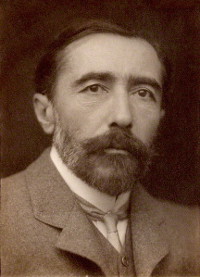

Though he spoke with a strong Polish accent throughout his life, with “years of devoted practice” his writing advanced him to the first rank of English novelists. Graham Greene declared him the best English stylist of the 20th century; T.E. Lawrence called him “absolutely the most haunting thing in prose that ever was.” Here’s his memory of that morning in Marseilles as he watched the English steamer depart:

Her head swung a little to the west, pointing towards the miniature lighthouse of the Jolliette breakwater, far away there, hardly distinguishable against the land. The dinghy danced a squashy, splashy jig in the wash of the wake and turning in my seat I followed the James Westoll with my eyes. Before she had gone in a quarter of a mile she hoisted her flag as the harbour regulations prescribe for arriving and departing ships. I saw it suddenly flicker and stream out on the flagstaff. The Red Ensign! In the pellucid, colourless atmosphere bathing the drab and grey masses of that southern land, the livid islets, the sea of pale glassy blue under the pale glassy sky of that cold sunrise, it was as far as the eye could reach the only spot of ardent colour — flamelike, intense, and presently as minute as the tiny red spark the concentrated reflection of a great fire kindles in the clear heart of a globe of crystal. The Red Ensign — the symbolic, protecting warm bit of bunting flung wide upon the seas, and destined for so many years to be the only roof over my head.

“The truth of the matter is that my faculty to write in English is as natural as any other aptitude with which I might have been born,” he wrote in A Personal Record. “I have a strange and overpowering feeling that it had always been an inherent part of myself. English was for me neither a matter of choice nor adoption. The merest idea of choice had never entered my head.”