acapnotic

n. a nonsmoker

Month: December 2006

Little Boy Lost

In November 1890, 4-year-old Ottie Cline Powell was gathering firewood when he wandered away from his schoolhouse in Amherst County, Virginia. An extensive search couldn’t find him.

His body was found the following spring on the peak of Bluff Mountain in the Blue Ridge — 7 miles away, at an elevation of 3,372 feet.

Floating Saucers

This may be the first UFO photo ever taken. It’s half of a stereo photograph dating from 1871, showing a cigar-shaped ship over Mount Washington, N.H.

“Mystery airships” were floating ominously over America between 1896 and World War I, but neither the ships nor the witnesses had quite got the hang of things yet. In 1897 the Washington Times suggested that the dirigibles were “a reconnoitering party from Mars”; the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch agreed that “these may be visitors from Mars, fearful, at the last, of invading the planet they have been seeking.”

But other accounts said they were terrestrial airships piloted by mysterious humans. One of these supposedly told an Arkansas state senator that he was flying to Cuba to use his “Hotchkiss gun” to “kill Spaniards.” In Texas, witnesses told of meeting “five peculiarly dressed men” who had descended from the Lost Tribes of Israel; they had learned English from British explorer Hugh Willoughby’s ill-fated 1553 expedition to the North Pole.

Much of this is documented, but newspaper writers themselves were prone to practical jokes in that era, which makes the whole thing impossible to untangle. Plus, people seem to want to believe this stuff: In April 1897, hoaxers sent up a balloon made of tissue paper over Burlington, Iowa. The Des Moines Leader received reports that the ship had “red and green lights” and that “one reputable citizen swore he heard voices.” Oh well.

Nevermore

Seeing a red apple should increase your confidence that all ravens are black.

Why? Because the statement “All ravens are black” is logically equivalent to “All non-black things are non-ravens.” And seeing a red apple (or green grass) confirms this belief.

This is logically inescapable, even if it’s counterintuitive. It’s known as Hempel’s paradox.

Kaspar Hauser

On May 26, 1828, a 16-year-old boy wandered into Nuremberg. He appeared to have the mental development of a 6-year-old; he could not say where he had come from, only repeating the sentence “I want to be a knight, as my father was” and the name “Kaspar Hauser.”

Two letters carried by the boy implied that his widowed mother had given him up to the care of a laborer, who had raised him in a secluded room. He said he had spent most of his life in a tiny cell with a straw bed, fed only on bread and water and occupied only with a carved wooden horse. Occasionally he was drugged so that his clothes could be changed and his hair cut. A mysterious man would visit him on occasion, always careful to hide his face.

It was noted that Hauser bore a passing resemblance to the grand duke of Baden. Officially the house of Baden had no comment about his case (it doesn’t to this day), but it seems someone was anxious to silence him: In 1829 a hooded man attacked him with an ax, succeeding only in wounding him slightly, and four years later another stranger waylaid and stabbed him. He died three days later.

Searching the crime scene, police found a small black purse with a note: “Hauser will be able to tell you how I look, where I came from and who I am. To spare him from this task I will tell you myself. I am from … on the Bavarian border … My name is MLO.”

Hauser lies now in a country graveyard. His headstone reads, “Here lies Kaspar Hauser, riddle of his time. His birth was unknown, his death mysterious.”

Road Rage

Donald Duck’s license plate number is 313.

Nine to Five

Average annual working hours over eight centuries, compiled by Boston College sociologist Juliet Schor:

- British peasant, adult male, 13th century: 1,620 hours

- British casual laborer, 14th century: 1,440 hours

- British worker, Middle Ages, 2,309 hours

- British farmer-miner, adult male, 1400-1600: 1,980 hours

- Average British worker, 1840: 3,105-3,588 hours

- Average American worker, 1850: 3,150-3,650 hours

- Average American worker, 1987: 1,949 hours

- British manufacturing workers, 1988: 1,855 hours

- Average German worker, 2000: 1,362 hours

Oral Exam

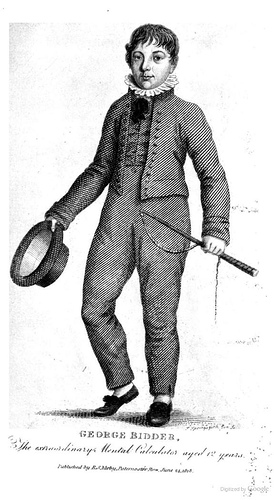

Math prodigy George Bidder was born to a Devonshire stonemason in 1806. In a public appearance at age 11, he answered each of these questions in less than a minute:

- What is the cube root of 673,373,097,125? “Answer, 8,765.”

- If a mouse can draw one ounce and a half, how many mice can draw 50,000 tons? “Answer, 1,194,666,666, and one ounce over.”

- If a coach travels from Exeter to Plymouth, 44 miles, every day in a year, how often does a wheel turn round that is 2 feet 9 inches? “Answer, 30,835,200.”

- If a fan of a windmill goes round 15 times in a minute, how many times will it go round in 7 years, 4 months, 1 week, 2 hours, 3 minutes — 365 days 6 hours to the year, and 28 days to the month? “Answer, 57,897,245.”

- If the ministers have taken of the income tax 12 millions of money in 1-pound notes, how many miles would they cover a road 30 feet wide, each note being 8 inches by 4 and a half? “He directly answered, 18 miles, 1,653 yards, and one foot.”

- Suppose the earth to consist of 971 million of inhabitants, and suppose they die in 33 years and four months, how many have returned to dust since the time of Adam, computing it to be 5,850 years? “Answer, 170,410,500,000.” Multiply it again by 99. “Answer, 16,870,639,500,000.”

(Reported in Kirby’s Wonderful and Scientific Museum, 1820)

Unquote

“There is hopeful symbolism in the fact that flags do not wave in a vacuum.” — Arthur C. Clarke

“Monkeys Demanding Their Dead”

Mr. Forbes tells a story of a female monkey (the Semnopithecus Entellus) who was shot by a friend of his, and carried to his tent. Forty or fifty of her tribe advanced with menacing gestures, but stood still when the gentleman presented his gun at them. One, however, who appeared to be the chief of the tribe, came forward, chattering and threatening in a furious manner. Nothing short of firing at him seemed likely to drive him away; but at length he approached the tent door with every sign of grief and supplication, as if he were begging for the body. It was given to him, he took it in his arms, carried it away, with actions expressive of affection, to his companions, and with them disappeared. It was not to be wondered at that the sportsman vowed never to shoot another monkey.

— Edmund Fillingham King, Ten Thousand Wonderful Things, 1860