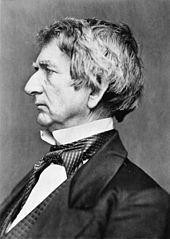

On Nov. 23, 1866, Secretary of State William Henry Seward inaugurated the first sustainable transatlantic telegraph line by sending a diplomatic cable. Seward’s message was a tidy 780 words, but he sent it using a Monroe cipher, which converted the text into groups of numbers. And the telegraph company stipulated that a coded message that used number groups had to spell out the numbers — so 387 was sent as THREE EIGHT SEVEN. Consequently Seward’s message expanded to 3,772 words. To add insult to injury, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company charged double, or $5 per word, for coded messages. Seward’s telegram ended up costing $19,540.40, more than three times his salary.

Seward refused to pay at first, but he lost a court fight. The editor of the New York Herald wrote sarcastically, “It is a shame for the United States government not to be able to pay its telegraph bills as promptly as a New York newspaper.”

(Ralph E. Weber, “Seward’s Other Folly: America’s First Encrypted Cable,” Studies in Intelligence 36 [1992], 105-109.) (Thanks, John.)