The Icelandic word gluggaveður (literally, “window weather”) means weather that looks appealing from indoors but would be unpleasant to go abroad in.

One of Haggard Hawks’ obscure words.

The Icelandic word gluggaveður (literally, “window weather”) means weather that looks appealing from indoors but would be unpleasant to go abroad in.

One of Haggard Hawks’ obscure words.

Linguist Ghil’ad Zuckermann writes homophonous poems: One part written in Israeli Hebrew sounds the same as another written in Italian, and both make sense.

(In my notes I see that the same example appeared in Word Ways in November 2003.)

Adam Thirlwell’s 2012 novel Kapow! and Mark Z. Danielewski’s 2000 House of Leaves (above) are typeset unconventionally, with some text appearing in separate blocks, aslant, and even upside down.

To create his 2010 book Tree of Codes, Jonathan Safran Foer took Bruno Schulz’s 1934 short story collection The Street of Crocodiles and physically cut out most of the words to produce a new story.

Marc Saporta’s 1962 novel Composition No. 1 consists of 150 unbound pages that can be read in any order.

Anne Carson’s 2010 Nox is an accordion-folded facsimile of a handmade book of memories of her brother, including old letters, family photos, and sketches.

Holes have been cut in several of the pages in B.S. Johnson’s 1964 novel Albert Angelo, allowing the reader to glimpse events further ahead in the story.

The plot of Serbian novelist Milorad Pavić’s 1988 Landscape Painted With Tea is constructed like a crossword puzzle, with chapters that can be read “across” or “down.” “The solution of the puzzle is supposed to lead to the solution of life.”

In the year 1611, when the King James Version of the Bible was published, William Shakespeare was 46 and 47 years old. The 46th word from the start of the 46th Psalm is shake, and the 47th word from the end is spear. Also, the 14th word is will, and the 32nd word from the end is am, preceded by I. And 14 + 32 = 46.

Remarkably, these coincidences obtain also in Richard Taverner’s 1539 Bible, which uses a different wording.

(J. Karl Franson, “A Myth About the Bard,” Word Ways 27:3 [August 1994], 154.)

In 2001, Toronto translator Sonja Elen Kisa invented a language, “my attempt to understand the meaning of life in 120 words.” She called it Toki Pona (“good language”) and focused on minimalism, trying to find the smallest core vocabulary needed to communicate. With only 120–125 root words and 14 phonemes, the language helps its speakers to concentrate on basic things and to think positively — Kisa told the Los Angeles Times, “It has sort of a Zen or Taoist nature to it.”

To her own surprise it’s begun to grow. By 2007 Kisa estimated that 100 people spoke Toki Pona fluently, and it’s since expanded in online forums, social media, and even hacked video games. Here’s the Lord’s Prayer:

mama pi mi mute o, sina lon sewi kon.

nimi sina li sewi.

ma sina o kama.

jan o pali e wile sina lon sewi kon en lon ma.

o pana e moku pi tenpo suno ni tawa mi mute.

o weka e pali ike mi. sama la mi weka e pali ike pi jan ante.

o lawa ala e mi tawa ike.

o lawa e mi tan ike.

tenpo ali la sina jo e ma e wawa e pona.

Amen.

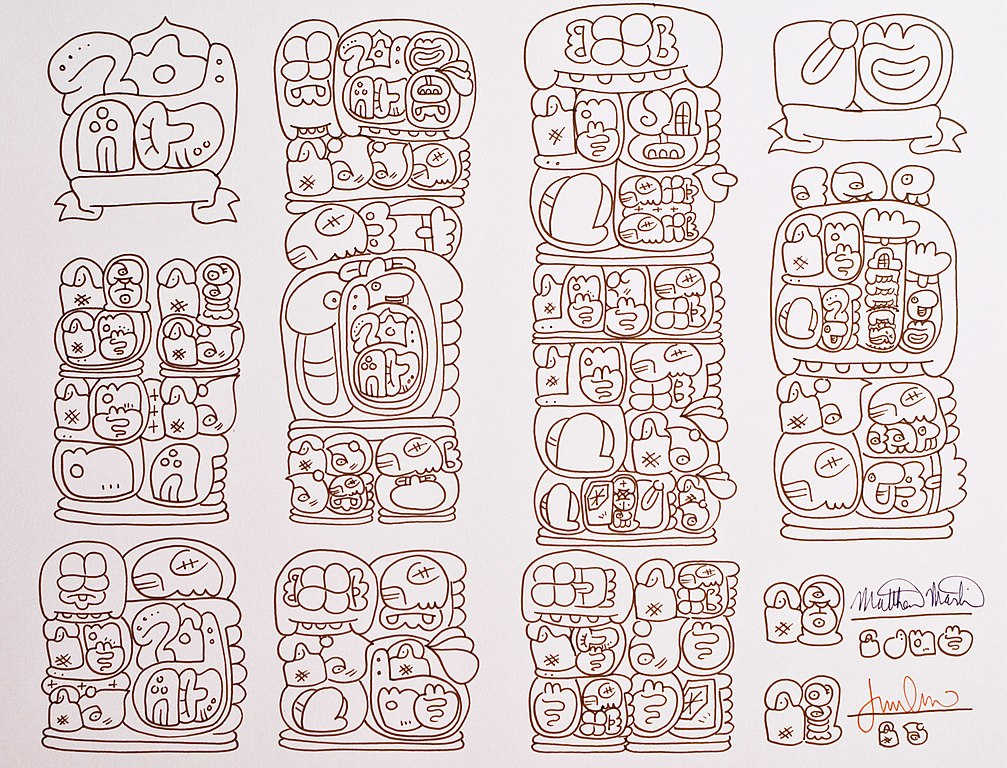

And above is a contract written by Jonathan Gabel in the sitelen sitelen writing system, arranging for sale of the contract itself as a piece of art. Official site, dictionary, language course.

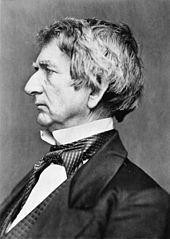

On Nov. 23, 1866, Secretary of State William Henry Seward inaugurated the first sustainable transatlantic telegraph line by sending a diplomatic cable. Seward’s message was a tidy 780 words, but he sent it using a Monroe cipher, which converted the text into groups of numbers. And the telegraph company stipulated that a coded message that used number groups had to spell out the numbers — so 387 was sent as THREE EIGHT SEVEN. Consequently Seward’s message expanded to 3,772 words. To add insult to injury, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company charged double, or $5 per word, for coded messages. Seward’s telegram ended up costing $19,540.40, more than three times his salary.

Seward refused to pay at first, but he lost a court fight. The editor of the New York Herald wrote sarcastically, “It is a shame for the United States government not to be able to pay its telegraph bills as promptly as a New York newspaper.”

(Ralph E. Weber, “Seward’s Other Folly: America’s First Encrypted Cable,” Studies in Intelligence 36 [1992], 105-109.) (Thanks, John.)

In 1902, scam artist Cassie Chadwick convinced an Ohio lawyer that she was the illegitimate daughter of steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. She parlayed this reputation into a life of unthinkable extravagance — until her debts came due. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe Chadwick’s efforts to maintain the ruse — and how she hoped to get away with it.

We’ll also encounter a haunted tomb and puzzle over an exonerated merchant.

There is a famous Israeli singer called Shlomi Shabat. I have jocularly named him for years Placido Domingo since [Shlomi] means peaceful (from shalom, ‘peace’) and [shabat] is Sabbath (the Jews’ Sunday). Placido Domingo is Spanish for ‘peaceful Sunday.’

— Ghil’ad Zuckermann, in Word Ways 32:1, February 1999

In 1854, a correspondent wrote to Notes and Queries asking about the origins of this couplet:

Perturbabantur Constantinopolitani

Innumerabilibus sollicitudinibus.

[“Constantinople is much perturbed.”]

He got this reply:

“When I first learned to scan verses, somewhere about thirty years ago, the lines produced by your correspondent P. were in every child’s mouth, with this story attached to them. It was said that Oxford had received from Cambridge the first line of the distich, with a challenge to produce a corresponding line consisting of two words only. To this challenge Oxford replied by sending back the second line, pointing out, at the same time, the false quantity in the word Constantinŏpolitani.”

Reader Eliot Morrison, a protein biochemist, has been looking for the longest English word found in the human proteome — the full set of proteins that can be expressed by the human body. Proteins are chains composed of amino acids, and the most common 20 are represented by the letters A, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, and Y. “These amino acids have different chemical properties,” Eliot writes, “and the sequence influences how the whole chain folds in three dimensions, which in turn determines the structural and functional properties of the protein.”

The longest English word he’s found is TARGETEER, at nine letters, in the uncharacterized protein C12orf42. The whole sequence of C12orf42 is:

MSTVICMKQR EEEFLLTIRP FANRMQKSPC YIPIVSSATL WDRSTPSAKH IPCYERTSVP CSRFINHMKN FSESPKFRSL HFLNFPVFPE RTQNSMACKR LLHTCQYIVP RCSVSTVSFD EESYEEFRSS PAPSSETDEA PLIFTARGET EERARGAPKQ AWNSSFLEQL VKKPNWAHSV NPVHLEAQGI HISRHTRPKG QPLSSPKKNS GSAARPSTAI GLCRRSQTPG ALQSTGPSNT ELEPEERMAV PAGAQAHPDD IQSRLLGASG NPVGKGAVAM APEMLPKHPH TPRDRRPQAD TSLHGNLAGA PLPLLAGAST HFPSKRLIKV CSSAPPRPTR RFHTVCSQAL SRPVVNAHLH

And there are more: “There are also a number of eight-letters words found: ASPARKLE (Uniprot code: Q86UW7), DATELESS (Q9ULP0-3), GALAGALA (Q86VD7), GRISETTE (Q969Y0), MISSPEAK (Q8WXH0), REELRALL (Q96FL8), RELASTER (Q8IVB5), REVERSAL (Q5TZA2), and SLAVERER (Q2TAC2).” I wonder if there’s a sentence in us somewhere.

(Thanks, Eliot.)