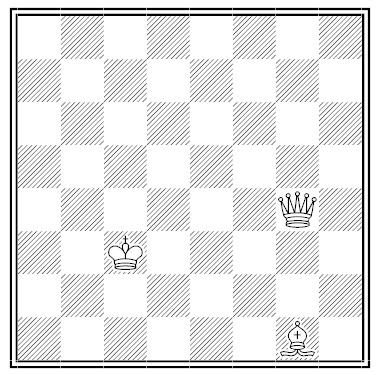

By Sam Loyd. Place the black king (a) where it can be checkmated on the move, (b) where it’s in stalemate, (c) where it’s in checkmate, and (d) where the three white pieces can’t be arranged to checkmate it.

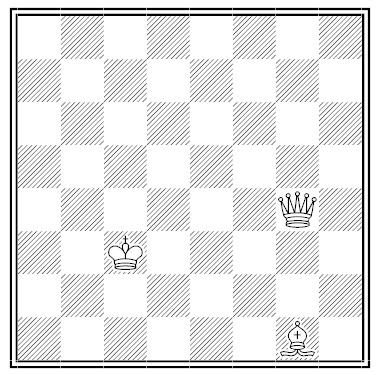

By Sam Loyd. Place the black king (a) where it can be checkmated on the move, (b) where it’s in stalemate, (c) where it’s in checkmate, and (d) where the three white pieces can’t be arranged to checkmate it.

Sam Goldwyn entered show business as Sam Goldfish.

In 1916 he formed a production company with Edgar Selwyn, and the two combined their names to form Gold-Wyn Pictures.

Critics pointed out that the alternative would have been “Selfish Pictures.”

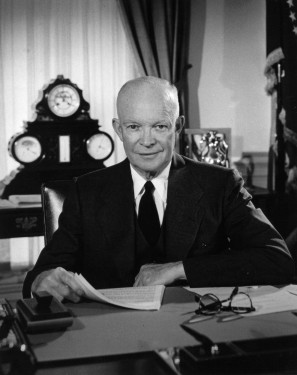

Dwight Eisenhower’s elliptical speaking style exasperated the Washington press corps. Journalist Oliver Jensen rewrote the Gettysburg Address as Ike would have delivered it:

I haven’t checked these figures, but 87 years ago, I think it was, a number of individuals organized a governmental setup here in this country, I believe it covered certain eastern areas, with this idea they were following up based on a sort of national independence arrangement and the program that every individual is just as good as every other individual. Well, now, of course, we are dealing with this big difference of opinion, civil disturbance you might say, although I don’t like to appear to take sides or name any individuals, and the point is naturally to check up, by actual experience in the field, to see whether any governmental setup with a basis like the one I was mentioning has any validity and find out whether that dedication by those early individuals will pay off in lasting values and things of that kind. …

Now frankly, our job, the living individuals’s job here, is to pick up the burden and sink the putt they made these big efforts here for. It is our job to get on with the assignment–and from these deceased fine individuals to take extra inspiration, you could call it, for the same theories about the setup for which they made such a big contribution. We have to make up our minds right here and now, as I see it, that they didn’t put out all that blood, perspiration and–well–that they didn’t just make a dry run here, and that all of us here, under God, that is, the God of our choice, shall beef up this idea about freedom and liberty and those kind of arrangements, and that government of all individuals, by all individuals and for the individuals, shall not pass out of the world-picture.

When Ida, the famous ostrich at the London Zoological Gardens, died in 1927, a post-mortem showed that she’d eaten too many foreign objects offered by visitors. Her stomach contained:

“It seems to us that the Associated Press is very profligate with its cable tolls these days,” observed one New York newspaper that picked up the story. “Why didn’t the correspondent say the ostrich had swallowed a stray Ford and be done with it?”

“Oh, slip on something and come down quick!”

His wife exclaimed with a frightened air.

He did: and he feels he has been played a trick–

For he slipped on a rug at the top of the stair.

— Bert Leston Taylor, collected in A Book of American Humorous Verse, 1917

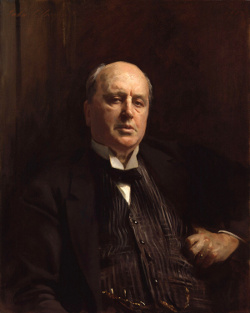

Despite his literary brilliance, Henry James was absurdly prolix in his daily life. Reportedly he once asked a waiter to “bring me … fetch me … carry me … supply me … in other words (I hope you are following me) serve–when it is cooked … scorched … grilled I should say–a large … considerable … meaty (as opposed to fatty) … chop.”

Once while motoring through England with Edith Wharton, James lost his way and hailed an old man at the side of the road. “My good man, if you’ll be good enough to come here, please; a little nearer–so. My friend, to put it to you in two words, this lady and I have just arrived here from Slough; that is to say, to be more strictly accurate, we have recently passed through Slough on our way here, having actually motored to Windsor from Rye, which was our point of departure; and the darkness having overtaken us, we should be much obliged if you would tell us where we now are in relation, say, to the High Street, which, as you of course know, leads to the Castle, after leaving on the left hand the turn down to the railway station.”

The old man looked blank. “In short, my good man,” said James, “what I want to put to you in a word is this: Supposing we have already (as I have reason to think we have) driven past the turn down to the railway station (which in that case, by the way, would probably not have been on our left hand, but on our right), where are we now in relation to–”

“Oh, please,” said Wharton, “do ask him where the King’s Road is.”

“Ah–? The King’s Road? Just so! Quite right! Can you, as a matter of fact, my good man, tell us where, in relation to our present position, the King’s Road exactly is?”

“Ye’re in it,” said the man.

An American reporter discovered this inscription on the wall of a Verdun fortress in 1945:

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1918

Austin White–Chicago, Ill.–1945

This is the last time I want to write my name here.

remugient

adj. bellowing again

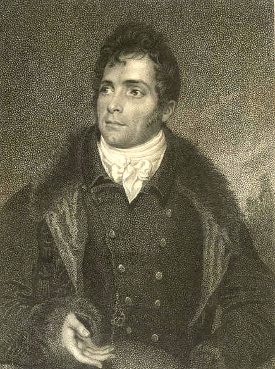

Robert Coates (1772-1848) achieved his dream of becoming a famous actor. Unfortunately, he was famous for being bad — like William McGonagall, Coates was so transcendently, world-bestridingly awful at his chosen craft that he attracted throngs of jeering onlookers.

In one performance of Romeo and Juliet, when he gave his exit line, “O, let us hence; I stand on sudden haste,” his diamond-spangled costume dropped a buckle and he began to hunt for it on hands and knees. “Come off, come off!” hissed the stage manager. “I will as soon as I have found my buckle,” he replied.

And that was a good night. He regularly improvised his lines; he took snuff during Juliet’s speeches and shared it with the audience; he tried to break into the Capulet tomb with a crowbar; he was pelted with carrots and oranges; he dragged Juliet from the tomb “like a sack of potatoes”; and he died on request, several times a night, always first sweeping the stage with his handkerchief. (“You may laugh,” he told one audience, “but I do not intend to soil my nice new velvet dress upon these dirty boards.”)

Once, having been killed in a stage duel, he overheard one woman wonder whether his diamonds were real. He sat up, bowed to her, said, “I can assure you, madam, on my word and honor they are,” and died again.

‘”No,” she laughed.’ How on earth could that be done? If you try to laugh and say ‘No’ at the same time, it sounds like neighing — yet people are perpetually doing it in novels. If they did it in real life they would be locked up.

— Hilaire Belloc, “On People in Books,” 1910