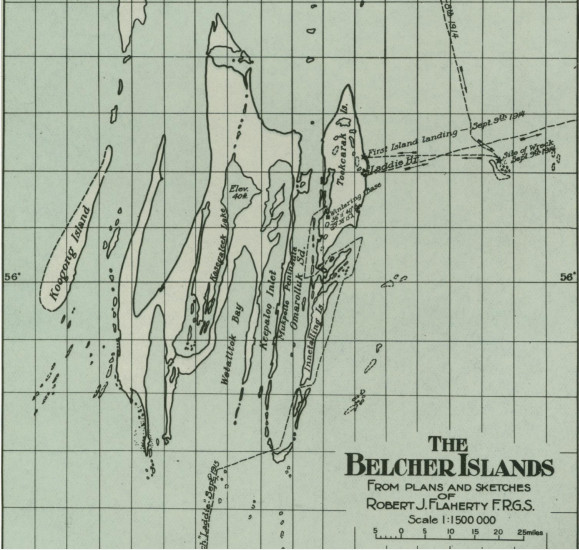

Before 1914, white explorers of Hudson’s Bay knew very little about the location, size, or number of the Belcher Islands — cartographers placed them on maps largely by guesswork, and some even doubted their existence.

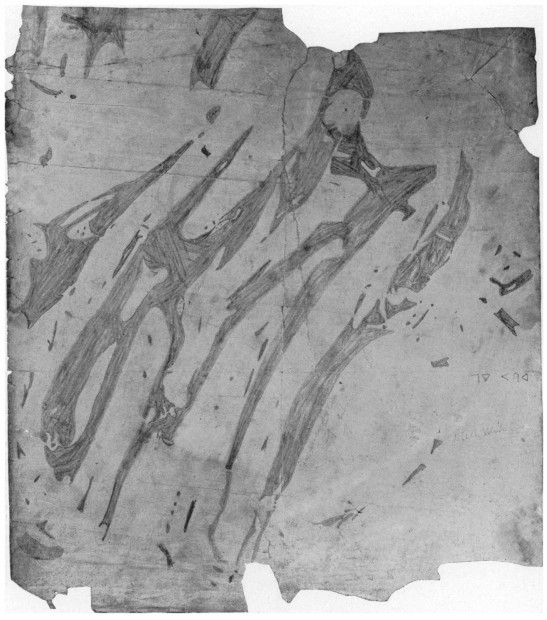

In 1895, an Inuit named Wetalltok sketched the map above on the back of an old missionary lithograph, but explorers remained skeptical. “That a land mass of such extent … could exist not a hundred miles to seaward of the centuries-old post at Great Whale River and remain unknown to the Hudson’s Bay Company seemed to me altogether improbable,” wrote anthropologist Robert J. Flaherty.

Only 20 years later, with Flaherty’s expedition of 1912-16, was the striking accuracy of Wetalltok’s map borne out (below). “In its grasp of the intricacies of the island system this map is a specially noteworthy example of its kind,” Flaherty wrote. “The Big Islands are ancient history in the bay now, and Wetalltok stands vindicated.”

(Robert J. Flaherty, “The Belcher Islands of Hudson Bay: Their Discovery and Exploration,” Geographical Review 5:6 [June 1918], 433-458.)