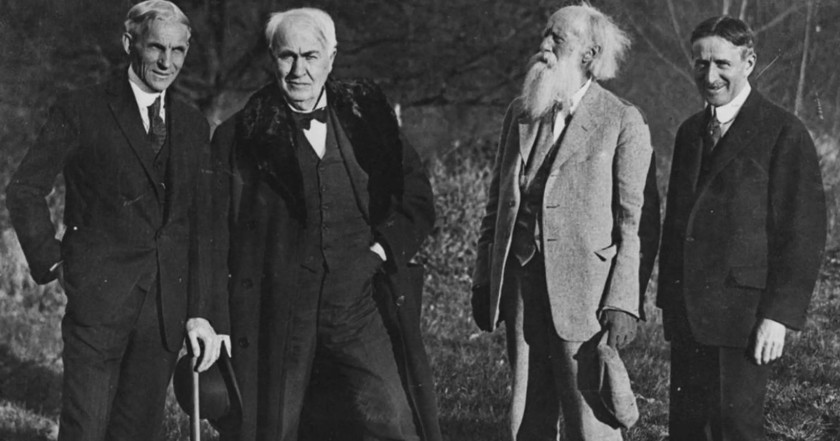

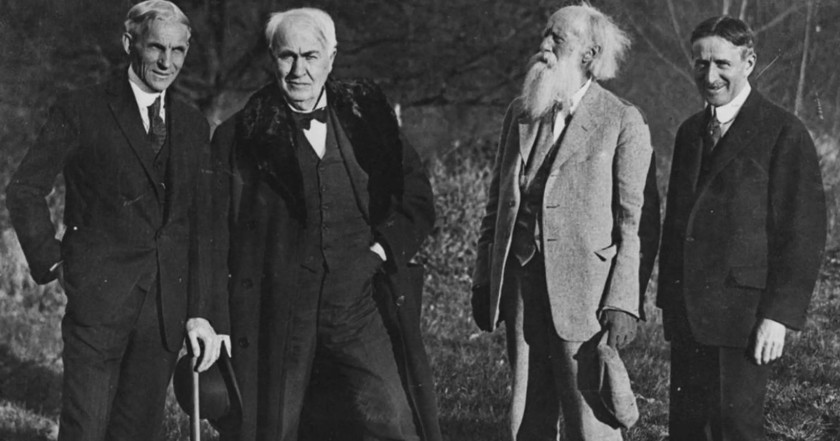

Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, John Burroughs, and Harvey Firestone used to take a camping trip each summer, calling themselves the Four Vagabonds. Ford liked to tell a story about stopping at a service station to replace a headlight:

He claimed to have said to the attendant, ‘By the way, you might be interested to hear that the man who invented this lamp is sitting out there in my car.’

‘You don’t mean Thomas Edison?’ the man gasped.

‘Yes, and, incidentally, my name is Henry Ford.’

‘Do tell! Good to meet you, Mr. Ford!’

Noting the brand of tire in the service station’s racks, Ford added, ‘And one of the other men in the car makes those tires — Firestone.’

The attendant’s jaw dropped. Then he saw John Burroughs with his flowing beard and his voice became skeptical: ‘Look here, mister, if you tell me that the old fellow with the whiskers out there is Santa Claus, I’m going to call the sheriff.’

(From Peter Collier and David Horowitz, The Fords: An American Epic, 2002. Thanks, Bill.)