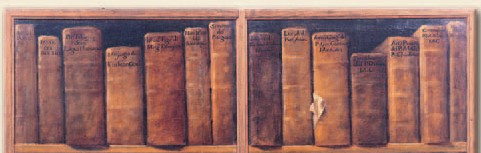

When University of Pennsylvania law professor Austin Tappan Wright died in a highway accident in 1931, he left behind a surprising legacy: an enormous novel about a nonexistent country. Wright had begun the project secretly as a young lawyer in the Boston office of Louis Brandeis, first preparing a 400-page summary of the country’s history, literature, peerage, and philosophy, as well as a detailed geography, contoured maps, weather, and import and export statistics. When Brandeis ascended to the Supreme Court Wright went on to teach at Berkeley and Penn, but none of his colleagues ever knew of the project.

Apparently Wright had found his own civilization lacking and devised this alternative as a sort of refuge. His hero, John Lang, becomes consul to the island nation, but rather than open it for trade he decides to remain there, “because the Islandian way is a better one. There a man is not split so that body and mind fall apart, the one going too far from earth, the other sinking too low in it. Here the labor which is regarded as the highest knows the realities on which men live only at second hand. We think too much about thoughts and not enough about feelings and things. Men specialize and deal with fragments and not with wholes. And our over intense brain life either desiccates the pure animal soul in man or makes an unmanlike beast of it. Desire becomes impure, perverse, a thing to be hidden and not to be faced.”

After Wright’s death, his wife typed out the 2,000-page manuscript, his daughter edited it down to a publishable length, and they put it out in 1942. We’ll never know what precisely it meant to its author, but the care he lavished on it is obvious. UCLA librarian Lawrence Clark Powell called it “one of the most completely documented imaginative works ever conceived,” and in the Pacific Spectator Kenneth Oliver wrote, “No other author of a utopian novel has known the land of his creation as intimately as Austin Wright knew Islandia.”