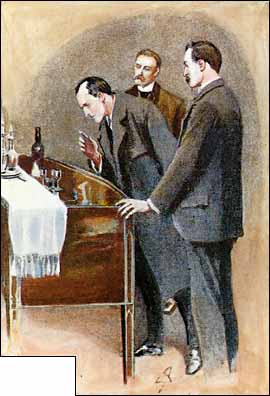

The title of this painting is electrifying: Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare Playing at Chess. Unfortunately, its authenticity has been subject to debate for more than a century. It came to light only in 1878, when it was purchased for $18,000 by Colonel Ezra Miller, and the authenticating documents were lost in a fire 17 years later.

Supporters claim that it was painted by Karel van Mander (1548-1606), and in the best possible case it would give us new likenesses of Jonson and Shakespeare painted by a contemporary. But a biography of van Mander, probably written by his brother, makes no mention of this painting, nor of the artist ever visiting London, and while Shakespeare here appears younger than Jonson, in fact he was eight or nine years older.

“It is understandable that there is still curiosity about Shakespeare’s life, physical features, and reputation,” wrote Roehampton Institute scholars Bryan Loughrey and Neil Taylor in 1983. “If the chess portrait were genuinely a portrait of Shakespeare and Jonson, the painting would be of unique interest. Unfortunately, most of the arguments that have been advanced in its favor are untenable.”

Real or fake, Shakespeare has the better of Jonson in this game — he can mate on the move:

(Bryan Loughrey and Neil Taylor, “Jonson and Shakespeare at Chess?” Shakespeare Quarterly 34:4 [Winter 1983], 440-448.)